About the time we get the first glimpse of the Pilgrim’s order of worship in 1612, Henry Ainsworth published his Book of Psalms. Containing lyrical and metrical versions of 39 Psalms from the Bible, it became the spiritual expression of musical joy brought by the Pilgrims to the new world 400 years ago. On July 20 when the Leyden Congregation met to say goodbye to that remnant of their congregation going to the new world, Edward Winslow noted the worship he heard in that final service together:

“They that stayed at Leyden feasted us that were to go at our pastor’s house, it being large; where we refreshed ourselves, after tears, with singing of Psalms, making joyful melody in our hearts as well as with the voice, there being many of our congregation very expert in music; and indeed it was the sweetest melody that ever mine ears heard.”

Note that the “experts” in music were part of the congregation. In Matthew 26:30 it is recorded “and when they had sung a hymn, they went out to the Mount of Olives.” In the Temple, only the Priests sang the songs. It is interesting that they (the disciples) sang the hymn, not just Jesus. The mark of the Reformation and doctrine of the Priesthood of the Believer restored the concept that the choir was the congregation, and thus the Pilgrims’ focus was on the participation of the people in worship. Historian Robert Bartlett explains the reason why only simple melodies (no harmony or instruments) were used:

It must be borne in mind that the Pilgrims were rebelling against a state church which had tight controls on every phase of worship, the slightest deviation from which was a punishable offense. To preach or pray from one’s own mind and heart was a new freedom. They discarded the use of the organ, the cross, and other church symbols, because they were tokens of oppression by kings and bishops.

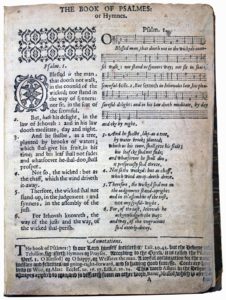

The first complete metrical Psalter in English, published in 1562, was known as “Sternhold and Hopkins.” Henry Ainsworth published his Psalter specifically for the Separatist Congregation in Holland. It remained as the main song book of the Pilgrims in Plymouth beyond 1692. Though “The Bay Psalm-Book”, published at Cambridge in 1640, and revised later, is better known, it is important to remember that Ainsworth’s contribution to the Pilgrim Church was unique.

The first complete metrical Psalter in English, published in 1562, was known as “Sternhold and Hopkins.” Henry Ainsworth published his Psalter specifically for the Separatist Congregation in Holland. It remained as the main song book of the Pilgrims in Plymouth beyond 1692. Though “The Bay Psalm-Book”, published at Cambridge in 1640, and revised later, is better known, it is important to remember that Ainsworth’s contribution to the Pilgrim Church was unique.

Henry Ainsworth was born about 1570, studied at Cambridge, and then joined the Separatist movement. Suffering for his beliefs, he fled to Amsterdam in 1593. In time, he became the Teacher in the Reformed congregation at Amsterdam. Pastor Robinson had good relations with this Church but chose to take his Separatist Congregation to Leyden to escape the controversies brewing in Amsterdam. Henry was known for his Biblical scholarship, particularly his understanding of Hebrew along with his subsequent Commentaries on the Old Testament. He passed away in 1623.

It is interesting to note that at least three ingredients make Ainsworth’s Psalter and Pilgrim worship unique. First, its translation (and notes of interpretation) of the Scriptures kept the lyrics as close to the original text as possible. Henry Ainsworth’s challenge was to take the Old Testament Psalms and turn the words into prose that could be set to an easy melody. Consider Psalm 23:1-3 as an example:

| Scripture Text of Psalm 23:1-3

Jehovah feedeth me; I shall not lack In folds of budding grass he maketh me lie down; He easily leadeth me by the waters of rests. He returneth my soul; He leadeth me in the beaten paths of justice for His name’s sake. |

Ainsworth’s Psalm 23:1-3 to be sung

Jehovah feedeth me, I shall not lack; In grassy folds He down dooth make me lye; He gently leads me quiet waters by. He dooth return my soul; for His name sake In paths of justice leads me quietly. |

Second, the prose of Scripture was inseparably connected to the melodies employed by Ainsworth. These were taken from a blend English, Dutch and French tunes used in the Reformed Churches dwelling in Amsterdam. Ainsworth put it this way; “Tunes for the Psalms I find none set of God; so that each people is to use the most grave, decent and comfortable manner of singing that they know… The singing-notes, therefore, I have most taken from our former Englished Psalms, when they will fit the measure of the verse. And for the other long verse I have also taken (for the most part) the gravest and easiest tunes of the French and Dutch Psalmes.”

Second, the prose of Scripture was inseparably connected to the melodies employed by Ainsworth. These were taken from a blend English, Dutch and French tunes used in the Reformed Churches dwelling in Amsterdam. Ainsworth put it this way; “Tunes for the Psalms I find none set of God; so that each people is to use the most grave, decent and comfortable manner of singing that they know… The singing-notes, therefore, I have most taken from our former Englished Psalms, when they will fit the measure of the verse. And for the other long verse I have also taken (for the most part) the gravest and easiest tunes of the French and Dutch Psalmes.”

Only the melodies are given in Ainsworth’s Psalm Book, and the C-clef alone is used. There are forty-eight tunes and where there is no tune given, the book refers to a tune already used in another Psalm. Nine are duplicates so that only 39 are needed to be memorized. The melody is set for the tenor and since several fonts were used it could be difficult to read. Some historians say the reason psalms were “lined”, where the leader sings a line and the congregation follows (see Ezra 3:11 for a Biblical example), is because not all families owned a Psalter and some may have had difficulty reading it.

Third, its rhythm was iambic (first beat on the second syllable). Trochaic (first beat on the first syllable) measures were not common until early in the 18th century. The tunes were often taken from folk songs and thus they were lively. Though the tunes were well known, it was intended that true worship would be from the heart, and the devotion of the Pilgrim Church to God through Christ made the songs come alive as does worship today when expressed from the heart.

Though Pilgrim worship did not include instruments, Bartlett writes “Undoubtedly some of the Pilgrims played instruments in England, Holland, and Plymouth. Music was an essential part of the heritage they brought with them across the ocean. They knew the madrigals and ballads that were popular in the homeland and sang them as they cooked and washed, cut timber, planted corn, and fed the cattle.”

Waldo Pratt, in his classic work The Music of the Pilgrims, published in 1921, makes the following observation about Pilgrim worship: Public worship as an institution was not only reverenced, but intensely loved, since it was the visible manifestation of the spiritual fraternity of believers in the presence and thought of God. It was known to be a positive means of grace largely because in it and through it the democratic congregationality of the brotherhood came to definite expression.

The faith of the Pilgrims, under the discipleship of Pastor John Robinson, was a unique expression of their theology. As Pratt writes “there began in the 17th century that impressive and lamentable change in liturgical emphasis through which ministeriality was exalted over congregationality… in consequence, the congregation came to regard its function as less that of activity, and sank into the attitude of the passive recipient.” This challenge of engaging the congregation remains with us today!