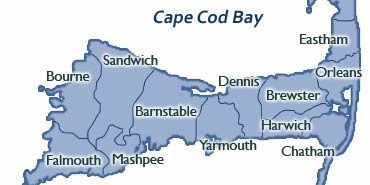

When exploring on Cape Cod, the Pilgrims desired to know everything they could about the Natives who already lived there. What they may not have known, however, was that in 1614, previous to their arrival, Thomas Hunt, an English trader, had taken over 20 Natives to Europe as slaves, leaving another stain upon the reputation of the English.

Curious as to the habits and lifestyle of the Natives, the Pilgrims began to dig up the graves they found. It was obvious their consciences became bothered, for they noted that they “left the rest untouched, because we thought it would be odious unto them to ransack their sepulchres.”

They also found corn buried in the sand. Knowing that what they brought with them would probably not grow in the sandy soil of New England, they wrote; “…we found a little old basket, full of fair Indian corn of this year, with some six and thirty goodly ears of corn, some yellow, and some red, and others mixed with blue, which was a very godly sight…” The Nauset tribe, owners of the graves as well as the corn, would not take kindly to this intrusion, especially after Hunt’s raid in 1614.

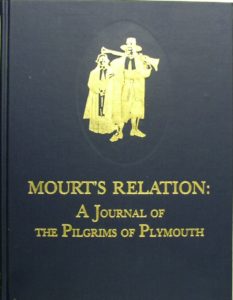

To the English, common law allowed one to “borrow” another’s property if in an emergency. But to the Nauset, it was a continuation of an assault. Mourt’s Relation, the Pilgrim’s diary, put it this way; “We were in suspense what to do with it and the kettle; and at length, after much consultation, we concluded to take the kettle, and as much of the corn as we could carry away with us; and when our shallop came, if we could find any of the people and come to parley with them, we would give them the kettle again, and satisfy them for their corn.” But how were the Nauset to know that this was their intention? Once putting the corn in the hold of the Mayflower, they wrote again; “…purposing, so soon as we could meet with any of the inhabitants of that place, to make them large satisfaction.”

To the English, common law allowed one to “borrow” another’s property if in an emergency. But to the Nauset, it was a continuation of an assault. Mourt’s Relation, the Pilgrim’s diary, put it this way; “We were in suspense what to do with it and the kettle; and at length, after much consultation, we concluded to take the kettle, and as much of the corn as we could carry away with us; and when our shallop came, if we could find any of the people and come to parley with them, we would give them the kettle again, and satisfy them for their corn.” But how were the Nauset to know that this was their intention? Once putting the corn in the hold of the Mayflower, they wrote again; “…purposing, so soon as we could meet with any of the inhabitants of that place, to make them large satisfaction.”

The Pilgrims were probably unaware of the fact that they were being watched from the woods. During their exploration, describing Friday, December 8, they wrote, “About five o’clock in the morning we began to be stirring… After prayer we prepared ourselves for breakfast, and for a journey…. Anon, all of a sudden, we heard a great and strange cry… One of our company… came running in, and cried, ‘they are men! Indians! Indians!’ and withal their arrows came flying amongst us.” The Nauset attacked in self-defense, but the Pilgrims may have had no idea the depth of offense already in place.

David Silverman writes “mutual good felling was one thing, but translating it into action was quite another… a series of minor crises gave both parties the chance to test the other’s commitment to the alliance. One such incident involved John Billington, a sixteen-year-old troublemaker from a troublemaking family, getting lost in the woods for five days before stumbling into the Wampanoag sachemship of Manomet, just southeast of Patuxet along the coast. The obvious thing for the Manomet Sachem, Canacum, to do would have been to return the boy straightway to the English. Instead, he delivered Billington to the sachem Aspinet of Nauset on Cape Cod, whose community the Mayflower passengers had ransacked in the weeks after their landing.”

Imagine! The older Billington boy, whose younger undisciplined brother nearly blew up the Mayflower playing with gunpowder, was now being held by the Nauset. History records how conflicts often result in war. To the great credit of both Massasoit, the Nauset and the English Pilgrims, this incident ended in reconciliation and helped to preserve the initial alliance of peace already established in March of 1621.

Bradford lead an expedition, probably in early August of 1621, arriving initially in what is now Barnstable Harbor. He sent native interpreters to communicate with the tribe there and they were told “that the boy was well, but he was at Nauset; yet since we were there, they desired us to come ashore… They brought us to their sachem, or governor, whom they call Iyanough, a man not exceeding twenty-six years of age, but very personable, gentle, courteous, and fair conditioned.”

Bradford lead an expedition, probably in early August of 1621, arriving initially in what is now Barnstable Harbor. He sent native interpreters to communicate with the tribe there and they were told “that the boy was well, but he was at Nauset; yet since we were there, they desired us to come ashore… They brought us to their sachem, or governor, whom they call Iyanough, a man not exceeding twenty-six years of age, but very personable, gentle, courteous, and fair conditioned.”

Mourt’s Relation then records the following: “One thing was very grievous unto us at this place. There was an old woman, whom we judged to be no less than a hundred years old, which came to see us, because she never saw English; yet could not behold us without breaking forth into great passion, weeping and crying excessively. We demanding the reason of it, they told us she had three sons, who, when Master Hunt was in these parts, went aboard his ship to trade with him, and he carried them captives into Spain, (for Tisquantum at that time was carried away also,), by which means she was deprived of the company of her children in her old age. We told them we were sorry that any Englishman should give them that offense, that Hunt was a bad man, and that all the English that heard of it condemned him for the same; but for us, we would not offer them any such injury, though it would gain us all the skins in the country. So we gave her some small trifles, which somewhat appeased her.

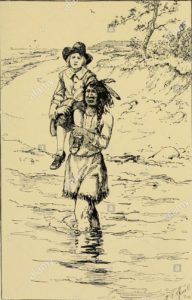

That apology set the stage for a successful return of John Billington from the Nauest as well as a reconciliation of offenses, especially to the owner of the corn they had taken. “Ere we came to Nauset… we promised him restitution, and desired him to either to come to Patuxet for satisfaction, or else we would bring them so much corn again. He promised to come… After sunset, Aspinet came with a great train, and brought the boy with him, one bearing him through the water. He had not less than a hundred with him; the half whereof came to the shallop side unarmed with him; the other stood aloof with their bows and arrows. There he delivered the boy, behung with beads, and made peace with us; we bestowing a knife on him, and likewise on another that first entertained the boy and brought him hither. So they departed from us.”

That apology set the stage for a successful return of John Billington from the Nauest as well as a reconciliation of offenses, especially to the owner of the corn they had taken. “Ere we came to Nauset… we promised him restitution, and desired him to either to come to Patuxet for satisfaction, or else we would bring them so much corn again. He promised to come… After sunset, Aspinet came with a great train, and brought the boy with him, one bearing him through the water. He had not less than a hundred with him; the half whereof came to the shallop side unarmed with him; the other stood aloof with their bows and arrows. There he delivered the boy, behung with beads, and made peace with us; we bestowing a knife on him, and likewise on another that first entertained the boy and brought him hither. So they departed from us.”

Bradford summarizes the incident this way, “Those people also came and made their peace; and they gave full satisfaction to those whose corn they had found and taken when they were at Cape Cod.” The lesson here is a simple one, yet unfortunately all too unique to history. It is critical that people on both sides of an offense, and in this case a serious one where 20 of one’s own were taken as slaves by another culture and nation, make the effort, in heart and action, to apologize and make things right. In this case, it helped to initially seal the alliance of peace that would last for over fifty years. We pray that in America today, we can reconcile differences rather than resort to the pattern of hostility, intolerance and hatred that so consistently arises in our land. May Christ’s warning be heard “Woe to the world because of offenses! For offenses must come, but woe to that man by whom the offense comes!” May our prayer be that “we give no offense in anything, that our ministry may not be blamed.”