Before the Pilgrims could navigate the waters of the Atlantic, they had to navigate the economic challenges of raising funds. They sought God at every turn in the face of financial obstacles. Though the 1606 Charter of James I for exploration had a mission of “propagating (the) Christian Religion,” it took God’s intervention to allow the Separatists permission to set up a colony. Wealthy merchants desired to finance voyages for revenue, but the cost was more money than they had, so they formed companies to limit liability. Two Virginia joint stock companies, both with royal patents, sought to colonize North America. The Virginia Company of London financed Jamestown in 1607. In the same year, the Virginia Company of Plymouth financed the Popham Colony in Maine. Unfortunately the Popham Colony was abandoned in nine months and the Plymouth Company went out of business by 1620.

However, the biggest obstacle the Pilgrims had was King James I, who wanted to “harry them out of the land” yet now they wanted permission to plant a colony in America. Proverbs 21:1 says, “The king’s heart is in the hand of the Lord, like the rivers of water; He turns it wherever He wishes.” Just as God parted the waters of the Red Sea, He played on the King’s desire for wealth and thus agreed to let them go. The first patent (royal permission) for the Pilgrims was from the Virginia Company of London. The Pilgrims, desiring to be far from Jamestown, intended to settle in the “northernmost parts of Virginia,” putting them near Manhattan. This Patent had to be re-done and the next was under the name of John Pierce. Thomas Weston, a 43 year old English merchant, came to Leiden in the spring and promised to finance the Pilgrims under the newly organized Council for New England. Weston proved to be a businessman who promised more than he could deliver, but since the Pilgrims were “knit together…in a… covenant of the Lord,” he thought it was a wise investment that might succeed.

However, the biggest obstacle the Pilgrims had was King James I, who wanted to “harry them out of the land” yet now they wanted permission to plant a colony in America. Proverbs 21:1 says, “The king’s heart is in the hand of the Lord, like the rivers of water; He turns it wherever He wishes.” Just as God parted the waters of the Red Sea, He played on the King’s desire for wealth and thus agreed to let them go. The first patent (royal permission) for the Pilgrims was from the Virginia Company of London. The Pilgrims, desiring to be far from Jamestown, intended to settle in the “northernmost parts of Virginia,” putting them near Manhattan. This Patent had to be re-done and the next was under the name of John Pierce. Thomas Weston, a 43 year old English merchant, came to Leiden in the spring and promised to finance the Pilgrims under the newly organized Council for New England. Weston proved to be a businessman who promised more than he could deliver, but since the Pilgrims were “knit together…in a… covenant of the Lord,” he thought it was a wise investment that might succeed.

The Pilgrim leaders began selling their homes in Leyden to finance their voyage. Each individual 16 and older would get 100 acres of land, the equivalent of a ten pound share. They could double their shares by bringing ten pounds of provisions. If a man brought his wife and children, each child 16 years and older would have a share, and those 10-15 would have half a share. A child under 10 would have no share but get 50 acres of land. If the family brought provisions, they could double their shares. This was a tremendous incentive for families!

The Pilgrim Fathers arrive at Plymouth, Massachusetts on board the Mayflower, November 1620. Painting by W.J. Aylward (Photo by Harold M. Lambert/Kean Collection/Archive Photos/Getty Images)

Even though they now had a financial contract and a patent, the Pilgrims conducted “a solemn meeting and a day of humiliation to seek the Lord for His direction” for relying on God was critical. Weston, in order to “insure” his financial success, changed two of the original contractual conditions without their knowledge. Robert Cushman, member of the church and agent, agreed to it out of fear, acting outside his jurisdiction “which was the cause afterward of much trouble and contention.”

The two changes tipped the scales heavily in favor of the Adventurers (financiers) rather than the Planters (those going). The Pilgrims wanted two days per week “for their own private employment… especially such as had families.” They also desired “the houses, & lands improved, especially gardens & home lots to remain undivided wholy to the planters at the 7 years’ end.” They had learned from Jamestown that private ownership was critical. Instead, they now had to work six days for the company and after seven years everything would be liquidated and distributed equally to both Planters and Adventurers. The Pilgrim leaders said this was “fitter for thieves & bondslaves than honest men.”

The Pilgrims hired the Mayflower but purchased the Speedwell. After a solemn assembly of prayer, they sailed from Leyden to London to join others. When the Speedwell sprung leaks they had to sell it for a loss. By the time the Mayflower set sail from Plymouth, England, they had lost time, supplies, people, and money. Bradford wrote “that their children may see with what difficulties their fathers wrestled in going through these things in their first beginnings, and how God brought them along.”

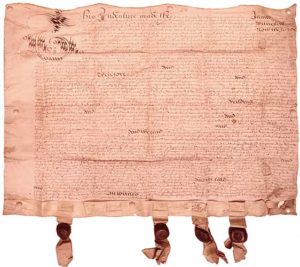

When the Pilgrims landed outside the jurisdiction of their patent, they wrote the Mayflower Compact as an act of self-government. Since the Compact had no force of law recognized by England, when the Mayflower returned in April of 1621, the Pilgrims requested another patent so they could remain where they were. The “Second Pierce Patent” has been preserved in Pilgrim Hall Museum. This patent was for seven years and allowed them to develop their own government and apply for a permanent charter once the seven years ended.

When the Pilgrims landed outside the jurisdiction of their patent, they wrote the Mayflower Compact as an act of self-government. Since the Compact had no force of law recognized by England, when the Mayflower returned in April of 1621, the Pilgrims requested another patent so they could remain where they were. The “Second Pierce Patent” has been preserved in Pilgrim Hall Museum. This patent was for seven years and allowed them to develop their own government and apply for a permanent charter once the seven years ended.

Their financial contract required the common field concept of shared land used in England to curb selfish profit. Though they tried for two years to implement it, Bradford wrote; “The experience that was had in this common course and condition, tried sundry years and that amongst godly and sober men… that the taking away of property and bringing in community into a commonwealth would make them happy and flourishing; as if they were wiser than God.”

The “common course” produced confusion, reduced employment and was thought to be “a form of slavery” having to work to provide for other’s who were lazy. In short, “it cut off those relations God hath set amongst men.” Thus, the leaders “assigned to every family a parcel of land, according to the proportion of their number… it made all hands very industrious, so as much more corn was planted than otherwise would have been.” But remember, even if one adopts the right economic structure, they must “pray that God would give them their daily bread.” Shortly, a drought nearly killed all of their crops.

So “they set apart a solemn day of humiliation, to seek the Lord by humble and fervent prayer.” Bradford relates “…(God) was pleased to give them a gracious and speedy answer, both to their own and the Indians’ admiration that lived amongst them.” Hobbomock, living nearby, was converted. As Dr. Wolfe points out, the results of this economic decision was that; “Each family was free at last to own its own land and keep its own production. The result, a tripling of the best previous output! Look at how much they planted year by year: in 1621, 26 acres; in 1622, 60 acres; in 1623, 184 acres!”

When the contract ended in 1627, the Pilgrims bought out the Adventurers for 1,800 pounds requiring a payment of 200 pounds per year. The Aptucxet Trading Post (1627) and the Jenney Grist Mill (1636) helped them pay off their debts by 1642. The trading post brought free trade with the Dutch and the Natives using wampum as currency. The mill allowed the private ownership of production. Providentially, both were seeds of the choice-based economic system in America that rests on the foundation of private ownership of land and labor, all started by this remnant church plant in America now called America’s Hometown!

When the contract ended in 1627, the Pilgrims bought out the Adventurers for 1,800 pounds requiring a payment of 200 pounds per year. The Aptucxet Trading Post (1627) and the Jenney Grist Mill (1636) helped them pay off their debts by 1642. The trading post brought free trade with the Dutch and the Natives using wampum as currency. The mill allowed the private ownership of production. Providentially, both were seeds of the choice-based economic system in America that rests on the foundation of private ownership of land and labor, all started by this remnant church plant in America now called America’s Hometown!