George Henry Boughton’s (1833-1905) painting Pilgrims Going to Church in 1867 was originally called The Early Puritans of New England Going to Church. Boughton was known as the “painter of New England Puritanism” and here portrayed the Pilgrim Church of men, women and children walking to the meetinghouse on guard in defense of their liberty. Notice the two men on the right, with one alerting the other, and some looking in the direction of a sound or disturbance coming from the woods.

When Isaack De Raisieres, chief trading agent for the Dutch West India Company, arrived in New Amsterdam (the Dutch colony in New York) in 1626, he desired to visit Plimoth Plantation. After a series of letters were exchanged, he did so in October of 1627. He described the way the Pilgrims reverently went to church to worship God. From 1921 until the present, the Town of Plymouth has re-enacted this eye-witness account and called it Pilgrim Progress.

“Upon the hill they have a large square house… The lower part they use for their church, where they preach on Sundays and the usual holidays. They assemble by beat of drum, each with his musket or firelock, in front of the captain’s door, they have their cloaks on, and place themselves in order, three abreast, and are led by a sergeant without beat of drum. Behind comes the Governor, in a long robe; beside him on the right hand, comes the preacher with his cloak on, and with a small cane in his hands; and so they march in good order, and each sets his arms down near him. Thus they are constantly on their guard night and day.”

“Upon the hill they have a large square house… The lower part they use for their church, where they preach on Sundays and the usual holidays. They assemble by beat of drum, each with his musket or firelock, in front of the captain’s door, they have their cloaks on, and place themselves in order, three abreast, and are led by a sergeant without beat of drum. Behind comes the Governor, in a long robe; beside him on the right hand, comes the preacher with his cloak on, and with a small cane in his hands; and so they march in good order, and each sets his arms down near him. Thus they are constantly on their guard night and day.”

Note the last sentence of De Raissiers’ eyewitness account. He described the Pilgrims progressing to meet but also “… constantly on their guard night and day.” De Raissiers could have been a spy sent by the Dutch and this may have piqued his interest. Though the Pilgrim Church was willing to express their faith “whatsoever it should cost them,” De Raissier noted they also were willing to defend it. If life, liberty of conscience, and the property on which to live it out is worth so much, it stands to reason that it would be worth defending. For the colonies in America, Jamestown (1607) and Plymouth (1620), together with the Natives of both regions, it was taken for granted that it was necessary to defend life, liberty and property.

Once establishing a place to settle, Bradford writes, “Saturday, the 17th day (of January) in the morning, we called a meeting for the establishing of military orders among ourselves; and we chose Miles Standish our captain, and gave him authority of command in affairs.” Though they had hired Miles Standish, he didn’t have authority to command military affairs until voted on by the people. This makes January 27 (new style), 1621 a significant date in the history of citizen militias for the United States. The citizen militia, often called “every man a soldier,” was directly answerable to the people at large, and always operated in submission to civil authority.

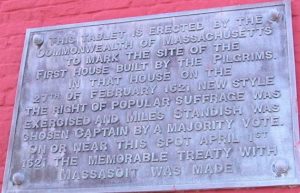

Consider the Peace Treaty with the Wampanoag that Massasoit ratified in March of 1621. It stated that the life (injury, hurt or death), liberty (unjust warfare) and property (anything taken away by either) would be justly defended. It also stated that when they would meet to discuss matters, they would leave their weapons behind them as a sign of peace. The site of the first common house is marked with a plaque that commemorates both of these significant developments in the history of Plymouth Colony.

Consider the Peace Treaty with the Wampanoag that Massasoit ratified in March of 1621. It stated that the life (injury, hurt or death), liberty (unjust warfare) and property (anything taken away by either) would be justly defended. It also stated that when they would meet to discuss matters, they would leave their weapons behind them as a sign of peace. The site of the first common house is marked with a plaque that commemorates both of these significant developments in the history of Plymouth Colony.

After Boston was settled in 1630, the same philosophy of citizen militia was established by Governor John Winthrop in 1638. The oldest chartered “Military Company of the Massachusetts” is now called the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company of Massachusetts. Its charter “proclaimed a recognition of public responsibility, the inherent right and duty of each citizen to defend those he loved, and the realization that only through properly organized training can these vital duties be efficiently discharged.” The concept of a citizen militia, answerable to the people and under the authority of the civil government, however, did not originate with the Pilgrims and Puritans.

In the Denver University Law Review, David Kopel writes, “New Englanders intensely self-identified with ancient Israel… Thus, ancient Hebrew militia law is part of the intellectual background of the American miltia system, and of the Second Amendment… Every male ‘from the age of twenty years up, all those in Israel who are able to bear arms’… were obliged to fight, to go forth ‘armed to battle.’” Rev. E. C. Wines describes a conversation he had with John Quincy Adams: “He drew, with a luminousness and power peculiar to himself, a contrast between Hebrew government and the other ancient oriental polities…. But that which he chiefly insisted on, was the fact, that all the rest were founded on force, this only on consent.”

In the Denver University Law Review, David Kopel writes, “New Englanders intensely self-identified with ancient Israel… Thus, ancient Hebrew militia law is part of the intellectual background of the American miltia system, and of the Second Amendment… Every male ‘from the age of twenty years up, all those in Israel who are able to bear arms’… were obliged to fight, to go forth ‘armed to battle.’” Rev. E. C. Wines describes a conversation he had with John Quincy Adams: “He drew, with a luminousness and power peculiar to himself, a contrast between Hebrew government and the other ancient oriental polities…. But that which he chiefly insisted on, was the fact, that all the rest were founded on force, this only on consent.”

And when did that freedom of consent, defended by a citizen militia under the control of civil government, originate on this soil? Wines writes, “The mystic harp was touched when the pilgrims set foot on Plymouth Rock. Its quivering strings discoursed their most eloquent music. The burden of the notes was, – human freedom; human brotherhood; human rights; the sovereignty of the people; the supremacy of law over will; the divine right of man to govern himself.”

On May 28, 1849, Robert C. Winthrop, descendant of Governor John Winthrop, gave an address at the annual meeting of the Massachusetts Bible Society in Boston. Winthrop had served as a Representative and Senator of the General Court in Massachusetts as well as Speaker of the House in Congress. He said words that each one of us ought to take to heart. The choice appears all too clear; we will either preserve our liberty to govern ourselves by consent or be controlled by a government of force.

All societies of men must be governed in some way or other. The less they may have of stringent State Government, the more they must have individual self-government. The less they rely on public law or physical force, the more they must rely on private moral restraint. Men, in a word, must necessarily be controlled, either by a power within them, or by a power without them; either by the word of God, or by the strong arm of man; either by the Bible, or the bayonet.