Thomas Faunce, born in 1646 in Plymouth, is the key individual who preserves the memory of the rock the Pilgrims stepped on when landing in Plymouth in December of 1620. The fifth of eight children, his father John arrived on the Anne in 1623 at about 15 years of age and was thus considered a “first comers.” By 1633, when John was 25, he married 18 year old Patience Morton (born in Leiden, Holland in 1615). His mother was raised as part of the Pilgrim Church under Pastor John Robinson. Thomas grew up hearing from his father about the rock on which the first comers landed on Monday, December 11, 1620.

The Faunce family had close ties to those who came on the Mayflower, particularly the Bradford family. When John Faunce died in 1653 at 47 years of age, Thomas was only 7, but William Bradford, his Dad’s friend, was alive at 63 and would live four more years. What a wealth of knowledge and respect must have surrounded Thomas as he grew up respecting the likes of William and Alice Bradford. Consider also that Thomas was nine when Myles Standish died, 26 when John Howland passed away, and 40 when John Alden was buried. All in all, 23 of the original Pilgrims were living in Thomas’ youth!

Alice, William Bradford’s second wife (his first, Dorothy, had drowned in Provincetown harbor soon after their arrival) continued being an example to Thomas after the death of her husband. In 1670 after Alice Bradford passed away, Thomas gave the eulogy on her life when he was 23, stating that he honored her “for her exertions in promoting the literary improvement and the deportment of the rising generation.” Thomas was a part of that rising generation and felt the torch was passing from the Bradford’s to youth like him.

Alice, William Bradford’s second wife (his first, Dorothy, had drowned in Provincetown harbor soon after their arrival) continued being an example to Thomas after the death of her husband. In 1670 after Alice Bradford passed away, Thomas gave the eulogy on her life when he was 23, stating that he honored her “for her exertions in promoting the literary improvement and the deportment of the rising generation.” Thomas was a part of that rising generation and felt the torch was passing from the Bradford’s to youth like him.

Thomas was chosen as a deacon of the First church in 1686 and then as an elder in 1694. As elder, he would lead the psalm singing line by line and the pastor would expound upon it. He was selected as the first clerk by the proprietors of Plymouth and Plympton Commons and was an integral part in keeping the records of the town of Plymouth. Perhaps the place where the Pilgrims landed was rehearsed at the 1720 commemoration of the landing when Rev. Ephraim Little, pastor of the First Church from 1699 to 1723, conducted a centennial celebration. Thomas, who was his lead Elder and worship leader, would surely have participated! Young people like Deacon Ephraim Spooner (1735-1818), who was a youth when Faunce identified Plymouth Rock, and others, attested to his character as well.

Thomas was chosen as a deacon of the First church in 1686 and then as an elder in 1694. As elder, he would lead the psalm singing line by line and the pastor would expound upon it. He was selected as the first clerk by the proprietors of Plymouth and Plympton Commons and was an integral part in keeping the records of the town of Plymouth. Perhaps the place where the Pilgrims landed was rehearsed at the 1720 commemoration of the landing when Rev. Ephraim Little, pastor of the First Church from 1699 to 1723, conducted a centennial celebration. Thomas, who was his lead Elder and worship leader, would surely have participated! Young people like Deacon Ephraim Spooner (1735-1818), who was a youth when Faunce identified Plymouth Rock, and others, attested to his character as well.

Such a servant within the First Church as an Elder and worship leader, as well as a public servant in keeping the town records, gave people plenty of evidence to confirm Faunce’s character that could be trusted. The value of private character becomes more valuable when something as important as recounting the first place where the Pilgrim Forefathers stepped is revealed. Perhaps this is Thomas’ greatest legacy, but it should be noted that it is only so because his character could be trusted. Well did Jesus say that “what I tell you in the dark, speak in the light” (Matthew 10:27) or in other words, you are never more in public than you are in private!

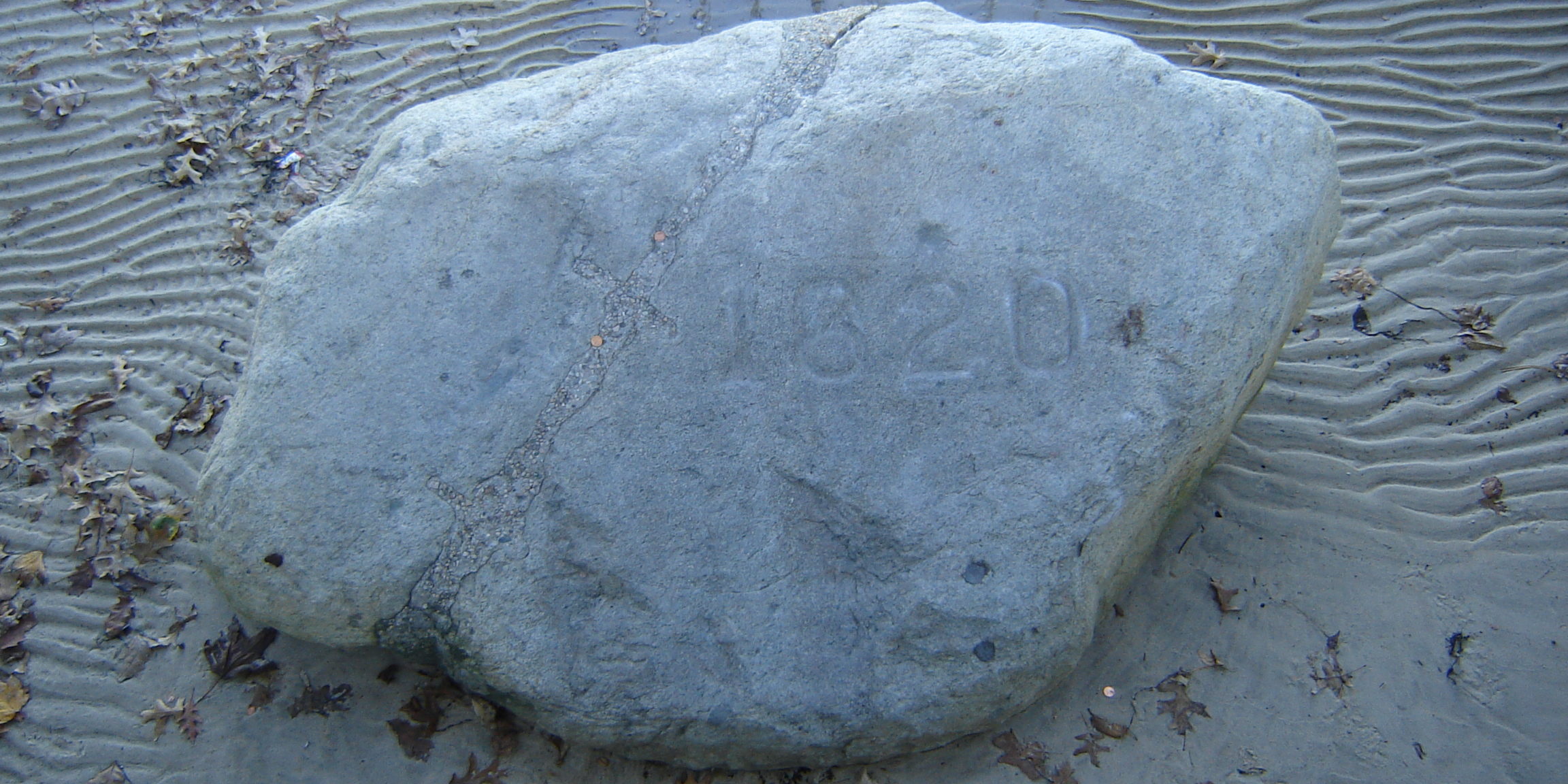

After Rev. Ephraim Little passed away in 1723, from 1724 to 1744 (when Thomas Faunce was 78-98) he assisted Rev. Nathaniel Leonard, the next pastor of First Church. In 1741, when Faunce was 95, he heard about a wharf that would be torn down in Plymouth and was moved to tears since the rock the Pilgrims first stepped on was underneath it. He was carried the three miles down to the wharf where a crowd gathered. James Thatcher, in his 1832 work on the History of Plymouth related the story: “Having pointed out the rock directly under the bank of Cole’s Hill, which his father had assured him was that which had received the footsteps of our fathers on their first arrival, and which should be perpetuated to posterity, he bedewed it with his tears and bid to it an everlasting adieu….” A simple marker was then placed to identify it.

After Rev. Ephraim Little passed away in 1723, from 1724 to 1744 (when Thomas Faunce was 78-98) he assisted Rev. Nathaniel Leonard, the next pastor of First Church. In 1741, when Faunce was 95, he heard about a wharf that would be torn down in Plymouth and was moved to tears since the rock the Pilgrims first stepped on was underneath it. He was carried the three miles down to the wharf where a crowd gathered. James Thatcher, in his 1832 work on the History of Plymouth related the story: “Having pointed out the rock directly under the bank of Cole’s Hill, which his father had assured him was that which had received the footsteps of our fathers on their first arrival, and which should be perpetuated to posterity, he bedewed it with his tears and bid to it an everlasting adieu….” A simple marker was then placed to identify it.

Thatcher also recounts what next happened in 1774. “The inhabitants of the town, animated by the glorious spirit of liberty… and mindful of the precious relick of our forefathers, resolved to consecrate the rock on which they landed to the shrine of liberty. Col. Theophilus Cotton, and a large number of inhabitants assembled, with about 30 yoke of oxen, for the purpose of its removal. The rock was elevated from its bed by means of large screws; and in attempting to mount it on the carriage it split asunder, without any violence. As no one had observed a flaw, the circumstances occasioned some surprise…. The separation of the rock was construed to be ominous of a division of the British Empire.” We now had two Plymouth Rocks!

Thatcher also recounts what next happened in 1774. “The inhabitants of the town, animated by the glorious spirit of liberty… and mindful of the precious relick of our forefathers, resolved to consecrate the rock on which they landed to the shrine of liberty. Col. Theophilus Cotton, and a large number of inhabitants assembled, with about 30 yoke of oxen, for the purpose of its removal. The rock was elevated from its bed by means of large screws; and in attempting to mount it on the carriage it split asunder, without any violence. As no one had observed a flaw, the circumstances occasioned some surprise…. The separation of the rock was construed to be ominous of a division of the British Empire.” We now had two Plymouth Rocks!

The top half of the Rock was moved next to the “Liberty Pole” during the Revolution. Then, in 1834, while being moved again on an ox cart, it fell off and split in two – we now had three Plymouth Rocks! It was eventually surrounded by an iron fence in front of Pilgrim Hall Museum (the oldest public museum in America). Tourists began coming to Plymouth in larger numbers and had access to this venerable object. They would chip off pieces and take them home as souvenirs and so we don’t know how many Plymouth Rocks there are! Many states and nations claim to have a chip off this old Rock! No wonder that the top half is now only a third of its original size!

The top half of the Rock was moved next to the “Liberty Pole” during the Revolution. Then, in 1834, while being moved again on an ox cart, it fell off and split in two – we now had three Plymouth Rocks! It was eventually surrounded by an iron fence in front of Pilgrim Hall Museum (the oldest public museum in America). Tourists began coming to Plymouth in larger numbers and had access to this venerable object. They would chip off pieces and take them home as souvenirs and so we don’t know how many Plymouth Rocks there are! Many states and nations claim to have a chip off this old Rock! No wonder that the top half is now only a third of its original size!

If Thomas Faunce had not been brought down to the wharf in 1741, we would probably not have identified the rock the Pilgrims stepped on. There would be no Hammett Billings canopy, completed in 1867 as tourists began to flood into Plymouth. Some say who cares? Like gravestones, we need tangible symbols that connect us to the past and the unwavering faith of our pilgrim ancestors. If a father had not related this story as a legacy to his son, we would have lost this legacy. Consider that Thomas would die at 99 years of age in 1744 at about the same time George Whitefield preached during the Great Awakening in Plymouth!

If Thomas Faunce had not been brought down to the wharf in 1741, we would probably not have identified the rock the Pilgrims stepped on. There would be no Hammett Billings canopy, completed in 1867 as tourists began to flood into Plymouth. Some say who cares? Like gravestones, we need tangible symbols that connect us to the past and the unwavering faith of our pilgrim ancestors. If a father had not related this story as a legacy to his son, we would have lost this legacy. Consider that Thomas would die at 99 years of age in 1744 at about the same time George Whitefield preached during the Great Awakening in Plymouth!

As Thomas Faunce bathed Plymouth Rock in tears, praying its tangible connection to the faith of his ancestors would not be lost, let us agree with Thatcher who wrote: “Standing on this rock… what honors shall we pay to the fathers of our country, the founders of that empire, which through ages shall remain the rich abode of knowledge, religion, freedom, and virtue! Criminal, indeed, would be our case were we not to cherish a religious sense of the exalted privileges inherited from our pious ancestors, and resolve to transmit them unimpaired to our children.”

As Thomas Faunce bathed Plymouth Rock in tears, praying its tangible connection to the faith of his ancestors would not be lost, let us agree with Thatcher who wrote: “Standing on this rock… what honors shall we pay to the fathers of our country, the founders of that empire, which through ages shall remain the rich abode of knowledge, religion, freedom, and virtue! Criminal, indeed, would be our case were we not to cherish a religious sense of the exalted privileges inherited from our pious ancestors, and resolve to transmit them unimpaired to our children.”