When William Bradford, over 10 years after the Pilgrims landed on Plymouth Rock, pondered the real mission of the Leyden Church migrating to the new world, he wrote that: “A great hope and inward zeal they had for the propagating and advancing the gospel of the kingdom of Christ in those remote parts of the world; yea, though they should be but even as stepping-stones unto others for the performing of so great a work.”

When William Bradford, over 10 years after the Pilgrims landed on Plymouth Rock, pondered the real mission of the Leyden Church migrating to the new world, he wrote that: “A great hope and inward zeal they had for the propagating and advancing the gospel of the kingdom of Christ in those remote parts of the world; yea, though they should be but even as stepping-stones unto others for the performing of so great a work.”

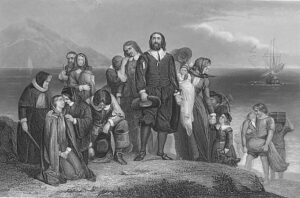

After their Thanksgiving service for answered prayer of rain (probably July 30, 1623), this mission of being stepping-stones began to take on reality. Following this service, as James Thacher writes, “…Two ships, the Ann and the Little James, arrived with supplies, and 60 passengers…. By these ships letters were received from their agent, Mr. Cushman, and from the adventurers.” Several from the Church in Leyden were on board, bringing supplies, and what a reunion of thanksgiving they must have had! Robert Cushman wrote, “Some few of your old friends are come; they come dropping to you, and by degrees; I hope ere long you shall enjoy them all.”

One of the adventurers wrote something that should have been received as an answer to prayer. Their mission to advance the Kingdom of God as stepping-stones to others was beginning to be realized. Half their number had died that first winter, but now their numbers were increasing! The note said:

“Let it not be grievous to you, that you have been instruments to break the ice for others, who come after with less difficulty; the honor shall be yours to the world’s end. We bear you always in our breasts, and our hearty affection is towards you all, as are the hearts of hundreds more, which never saw your faces, who doubtless pray for your safety as their own.”

One of the keys to being a stepping-stone is the continuation of the family. The difficulty of carving out a colony in the wilderness was recognized by the Plymouth colony, and that is why individuals that were single were put in family units and expected to marry, and those who had lost spouses were to remarry. One of the passengers on the Anne was Alice Carpenter Southworth, who had been in Leyden with the Separatist church there. Alice had two sons, Constant and Thomas, who would arrive in Plymouth sometime after 1627. After her husband, Edward, died, she and William Bradford wrote letters of courtship for some months since they knew each other well. William had lost Dorothy, his first wife, that first winter in 1621. Thacher puts their marriage on August 14, 1623.

Emmanuel Altham, who had arrived on the Little James, wrote his brother Sir Edward Altham, describing the civil ceremony (probably conducted by Assistant Isaac Allerton) in this way:

Emmanuel Altham, who had arrived on the Little James, wrote his brother Sir Edward Altham, describing the civil ceremony (probably conducted by Assistant Isaac Allerton) in this way:

“Upon the occasion of the Governor’s marriage… Massasoit was sent for to the wedding, where came with him his wife, the queen, although he hath five wives. With him came four other kings and about six score men with their bows and arrows – where, when they came to our town, we saluted them with the shooting off of many muskets and training our men…. and he brought the Governor three or four bucks and a turkey. And so we had very good pastime in seeing them dance, which is in such manner, with such noise that you would wonder…. And now to say somewhat of the great cheer we had at the Governor’s marriage. We had about twelve pasty venisons, besides others, pieces of roasted venison and other such good cheer in such quantity that I wish you some of our share. For here we have the best grapes that ever you say [saw] – and the biggest, and divers sorts of plums and nuts which our business will not suffer us to look for.”

As joyful as the colony was to celebrate with William and Alice and see how pioneering peace with the Wampanoag produced such friendship, Thacher comments that their friends were generally shocked at “the miserable condition of those who had been almost three years in the country…. ‘The best dish we could present them with,’ says Governor Bradford, ‘is a lobster or piece of fish, without bread, or anything else but a cup of fair spring water; and the long continuance of this diet, with our labors abroad, has somewhat abated the freshness of our complexions; but God gives us health.’”

In total, about 90 passengers were on the Anne and Little James, 60 of which were from the Leyden congregation. However, 30 passengers were independent, under John Oldham. They had been promised a separate living situation apart from the original plantation. The challenge of expansion has always required balancing rights and responsibilities. Though the Pilgrims were stepping-stones to prepare for others to follow, they faced a challenge described by Bradford: “The Old Planters were afraid that their corn, when it was ripe, should be imparted to the newcomers, whose provisions which they brought with them they feared would fall short before the year went about, as indeed it did.”

In total, about 90 passengers were on the Anne and Little James, 60 of which were from the Leyden congregation. However, 30 passengers were independent, under John Oldham. They had been promised a separate living situation apart from the original plantation. The challenge of expansion has always required balancing rights and responsibilities. Though the Pilgrims were stepping-stones to prepare for others to follow, they faced a challenge described by Bradford: “The Old Planters were afraid that their corn, when it was ripe, should be imparted to the newcomers, whose provisions which they brought with them they feared would fall short before the year went about, as indeed it did.”

The firstcomers agreed to wait till their own harvest of corn (being now private) and not use the provisions brought by the newcomers. If the newcomers wished to sell (or barter) some of their provisions, that was fine. Bradford writes, “Their request was granted them, for it gave both sides good content; for the newcomers were as much afraid that the hungry Planters would have ate up the provisions brought, and they should have fallen into like condition.” The balancing of rights and responsibilities preserves unity when all agree to submit to the same rule of law. The Old Planters agreed to pay for any provisions from the newcomers, and the newcomers agreed to help with the common defense, pay a bushel of Indian corn or its worth into the common store, and not trade with the Natives, but without bearing responsibility under the agreement with the Old Planters and Adventurers.

What was the result of this balance of rights and responsibilities in being “stepping-stones”? First, they were able to send the Anne back “laden with clapboard by the help of many hands. Also they sent in her all the beaver and other furs they had, and Mr. Winslow was sent over with her to inform of all things and to procure such things as were thought needful for their present condition.”

Bradford writes: “Instead of famine now, God gave them plenty, and the face of things was changed, to the rejoicing of the hearts of many, for which they blessed God. And the effect of their particular planting was well seen, for all had, one way and other, pretty well to bring the year about; and some of the abler sort and more industrious had to spare, and sell to others, so as any general want or famine hath not been amongst them since to this day.” This blessing was being a stepping-stone unto others!