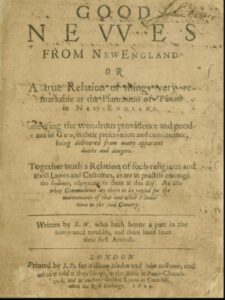

Four hundred years ago, Edward Winslow commented on the year 1623, writing in Good News from New England (originally published in 1624), “The month of April being now come, on all hands we began to prepare for corn. And because there was no corn left before this time, save that was preserved for seed, being also hopeless of relief by supply, we thought best to leave off all other works, and prosecute that as most necessary. And because there was no small hope of doing good, in that common course of labor…”

Four hundred years ago, Edward Winslow commented on the year 1623, writing in Good News from New England (originally published in 1624), “The month of April being now come, on all hands we began to prepare for corn. And because there was no corn left before this time, save that was preserved for seed, being also hopeless of relief by supply, we thought best to leave off all other works, and prosecute that as most necessary. And because there was no small hope of doing good, in that common course of labor…”

It was in April and probably May that a discussion ensued, as indicated by William Bradford: “So they began to think how they might raise as much corn as they could, and obtain a better crop than they had done, that they might not still thus languish in misery.”

You might remember that the agreement by which the Pilgrims were to operate was changed at the last moment before their voyage, having been forced into it by Thomas Weston. As I wrote in 2020:

“Weston, in order to ‘insure’ his financial success, changed two of the original contractual conditions…. Robert Cushman, member of the church and agent, agreed to it out of fear, acting outside his jurisdiction ‘which was the cause afterward of much trouble and contention.’ The two changes tipped the scales heavily in favor of the Adventurers (financers) rather than the Planters (those going). The Pilgrims wanted two days per week ‘for their own private employment… especially such as had families.’ They also desired ‘the houses, & lands improved, especially gardens & home lots to remain undivided wholy to the planters at the 7 years’ end.’ They had learned from Jamestown that private ownership was critical.

Instead, they now had to work six days for the Company, and after seven years everything would be liquidated and distributed equally to both Planters and Adventurers. The Pilgrim leaders said this was ‘fitter for thieves & bondslaves than honest men.’”

Article 10 of the new contract stated that “all such persons as are of this colony are to have their meat, drink, apparel, and all provisions out of the common stock and goods of the said colony.” In short, they were forced into what Bradford described as a “common course and condition,” which by 1623 was a major cause of their lack of production.

As Bradford wrote, describing the situation after two years of attempting to make it work, “The experience that was had in this common course and condition, tried sundry years and that amongst godly and sober men… that the taking away of property and bringing in community into a commonwealth would make them happy and flourishing, as if they were wiser than God.” The Pilgrims understood that private industry and a personal work ethic was not only Biblical, but the most practical for prosperity.

As Bradford wrote, describing the situation after two years of attempting to make it work, “The experience that was had in this common course and condition, tried sundry years and that amongst godly and sober men… that the taking away of property and bringing in community into a commonwealth would make them happy and flourishing, as if they were wiser than God.” The Pilgrims understood that private industry and a personal work ethic was not only Biblical, but the most practical for prosperity.

Bradford lists, from their experience, the failure of a communal system of economics (partial socialism, though the word was not in use at that time), and why, by contrast, the ingredients of economic liberty, as I summarized in my paper Economic Liberty: Legacy of the Pilgrims, was best:

1. In a common ownership of labor and land, people tend to become lazy, not wanting to work; thus, private property must undergird a free and productive economy.

2. Under socialism, people tend to make up excuses as to why they can’t work; thus, private profit is a key ingredient in a free economy as well.

3. Communal living breeds discontent, for all tend to want what others have, but refuse to work for it; thus, welfare must be voluntary (private charity) rather than forced (government charity).

4. Socialism is built on pride and a presumed external equality in an open or ignorant refusal of God’s plan in the Bible so that differences between the young, adult, or aged are not respected. In contrast, a free economy is built on the respect and dignity of individual differences.

5. Though some look at the profit motive as corrupt, it is imperative to see that it is man’s nature that is corrupt, including those who hold office in government. The free market, in contrast, is built on personal incentive and self-interest in order to overcome one’s naturally corrupt nature.

6. Ultimately, God’s design for the economy rests on voluntary choice, which is far more productive than government force and the re-distribution of wealth.

Bradford concludes this analysis with the fact that all men have this corruption (sinful and selfish nature), so God in His wisdom saw another course fitter for them. And what was that course?

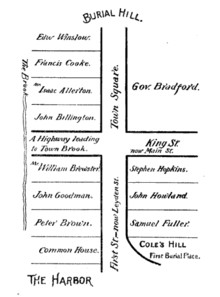

Bradford writes that after discussing the failure of the “common course and condition,” they assigned to every family a parcel of land, according to the proportion of their number. The result of having private property with personal incentive was that, “This had very good success, for it made all hands industrious, so as much more corn was planted than otherwise would have been by any means the Governor or any other could use, and saved him a great deal of trouble and gave far better content. The women went willingly into the field, and took their little ones with them to set corn; which before would allege weakness and inability; whom to have compelled would have been thought great tyranny and oppression.”

Bradford writes that after discussing the failure of the “common course and condition,” they assigned to every family a parcel of land, according to the proportion of their number. The result of having private property with personal incentive was that, “This had very good success, for it made all hands industrious, so as much more corn was planted than otherwise would have been by any means the Governor or any other could use, and saved him a great deal of trouble and gave far better content. The women went willingly into the field, and took their little ones with them to set corn; which before would allege weakness and inability; whom to have compelled would have been thought great tyranny and oppression.”

Charles Wolfe wrote, “Each family was free at last to own its own land and keep its own production. The result, a tripling of the best previous output! …in 1621, 26 acres; in 1622, 60 acres; in 1623, 184 acres!” Wolfe also writes, “Why were the Pilgrims so successful in acquiring new tools of production that multiplied their output and lifted their standard of living? Because, as practicing Christians, they overcame to a large extent fallen man’s sense of unlimited wants, combined with a severely limited sense of God’s provision… Thus, the Pilgrims refrained from devouring the seed corn; they saved and invested in new tools of production; and apparently were just as happy to pay investors a profit as they were to pay workers their wages.”

God has designed the free market to operate on self-regulation and not government intrusion. In this way, man’s selfish nature checks his greed with his responsibility to produce. The poor are best helped through private charity, where they are empowered to labor instead of becoming dependent. This operates best, of course, in an atmosphere where people are self-governed with Christian values of giving. As Bradford and the Pilgrims learned in 1623, 400 years ago, God’s wisdom is best.

In our next E-News article, to be published in June, we will see why the further ingredient of prayer and fasting is also critical in maintaining liberty in economics.