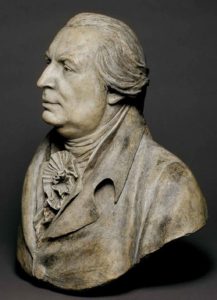

It was August 10, 1792, and American Ambassador Gouverneur Morris was in Paris. It was the day that the Monarchy of France would fall. Ever since July 14, 1789, when the Bastille was stormed, mob rule threatened to end the Monarchy. Once the King ordered the Swiss, who stood with their Monarch, to cease fire in the face of the mob, the palace was sacked and anarchy possessed the city. All who were friends or allies of the Monarchy were now in danger, and they turned to the American minister for protection. Morris, who had not fled with the other foreign ministers, remained faithful to his post. He was opposed to the tyrannical Monarchy, but he also became outraged at the methods of mob rule attempting to take its place, for “he felt a profound contempt for both sides.”

It was August 10, 1792, and American Ambassador Gouverneur Morris was in Paris. It was the day that the Monarchy of France would fall. Ever since July 14, 1789, when the Bastille was stormed, mob rule threatened to end the Monarchy. Once the King ordered the Swiss, who stood with their Monarch, to cease fire in the face of the mob, the palace was sacked and anarchy possessed the city. All who were friends or allies of the Monarchy were now in danger, and they turned to the American minister for protection. Morris, who had not fled with the other foreign ministers, remained faithful to his post. He was opposed to the tyrannical Monarchy, but he also became outraged at the methods of mob rule attempting to take its place, for “he felt a profound contempt for both sides.”

It was an age-old battle of extremes – tyranny and anarchy. However, Gouverneur Morris represented the balanced position, the third alternative, quite rare in history, of the rule of law, limited government, and God-given rights emerging from the American Revolution, set on the firm foundation of Biblical truth. As Henry Cabot Lodge noted, “He had been a leading patriot in our revolution; he had served in the Continental Congress, and with Robert Morris in the difficult work of the Treasury, when all our resources seemed to be at their lowest ebb. In 1788 he had gone abroad on private business, and had been much in Paris, where he had witnessed the beginning of the French Revolution.”

Morris was of both French and English descent, born in New York in 1752. His half-brother Lewis Morris was a signer of the Declaration. Gouverneur initially feared that the American Revolution would swing the pendulum from the tyranny of English Monarchy to the anarchy of mobs and tumult. When convinced that his own country sought to defend the God-given right asserted in the Declaration; “that whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness,” he joined the cause.

Morris was of both French and English descent, born in New York in 1752. His half-brother Lewis Morris was a signer of the Declaration. Gouverneur initially feared that the American Revolution would swing the pendulum from the tyranny of English Monarchy to the anarchy of mobs and tumult. When convinced that his own country sought to defend the God-given right asserted in the Declaration; “that whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness,” he joined the cause.

But a question has lingered throughout history. What kind of government will the people set up to replace tyranny? Also, what methods will be used to alter or to abolish it? Gouverneur strongly resisted anarchistic rule and stood for a strong national government, speaking 173 times during the Constitutional Convention, the most of any delegate. He was the one who wrote the final draft of the Constitution, improving its rhetoric and style and earning the title the “Penman of the Constitution.”

Morris had a love of liberty under law and a disdain for slavery. He said during the Convention in 1787, “Upon what principle is it that the slaves shall be computed in the representation? Are they men? Then make them citizens, and let them vote.” A Federalist, he also knew that a most important foundation was the rule of law where both people and leaders are bound by oath to the constitution. So on August 10 he now faced a dire dilemma, for though the Monarchy of France was a tyrannical state, the alternative now taking over the city of Paris had no oath to any law but anarchy.

Morris’ diary provides us with an eyewitness of the French Revolution and the pendulum swing between centralized tyranny on one hand and the people opposing it through anarchy. The Pilgrims faced such a dilemma in 1620. The tyranny of King James I “harried them out of the land.” The talk of mutiny on the Mayflower once landing outside their Charter threatened anarchy. We can be thankful that they instituted the alternative of a new government of self-government under the rule of law “for the glory of God and advancement of the Christian faith.”

Morris’ diary provides us with an eyewitness of the French Revolution and the pendulum swing between centralized tyranny on one hand and the people opposing it through anarchy. The Pilgrims faced such a dilemma in 1620. The tyranny of King James I “harried them out of the land.” The talk of mutiny on the Mayflower once landing outside their Charter threatened anarchy. We can be thankful that they instituted the alternative of a new government of self-government under the rule of law “for the glory of God and advancement of the Christian faith.”

This same dilemma of two extremes faced the early Church that followed the teachings of Jesus Christ. On one hand, Jesus taught against the centralized tyranny of Rome, exposing Gentile rule by force, and on the other extreme, he exposed the fallacy of anarchist violence of the Zealots. He told Peter to put away his sword, not as a rule, but because he was embracing the attitude of “living by the sword” as if the Kingdom of God advances by force. The answer was to allow the spirit of Christ to form self-governing churches with elected leaders, sowing the seeds of liberty for future generations.

An eyewitness of Morris’ conduct in 1792 reveals his unfailing devotion to liberty as well as duty, “On the ever memorable 10th of August… the writer thought it his duty to visit the Minister… He was surrounded by the old Count d’Estaing, and about a dozen other persons of distinction, of different sexes, who had, from their connection with the United States… taken refuge for protection from the bloodhounds… prowling the streets at the time.” Gouverneur said, “Whether my house will be protection to them or to me, God only knows, but I will not turn them out of it.” Gouverneur stayed at his post in spite of the danger. He did so to protect the innocent from the mob, as well as to continue his duty to represent the United States and its government to the French Monarchy.

In his own words: “The different ambassadors and ministers are all taking their flight, and if I stay I shall be alone… we have no right to prescribe to this country the government they shall adopt, and… because the basis of our own Constitution is the indefeasible right of the people to establish it… it has been broadly hinted to me that the honor of my country and my own require that I should go away. But I am of a different opinion, and rather think that those who give such hints are somewhat influenced by fear. It is true that the position is not without danger, but I presume that when the President did me the honor of naming me to this embassy, it was not for my personal pleasure or safety, but to promote the interest of my country. These, therefore, I shall continue to pursue to the best of my judgment, and as to consequences, they are in the hand of God.”

In his own words: “The different ambassadors and ministers are all taking their flight, and if I stay I shall be alone… we have no right to prescribe to this country the government they shall adopt, and… because the basis of our own Constitution is the indefeasible right of the people to establish it… it has been broadly hinted to me that the honor of my country and my own require that I should go away. But I am of a different opinion, and rather think that those who give such hints are somewhat influenced by fear. It is true that the position is not without danger, but I presume that when the President did me the honor of naming me to this embassy, it was not for my personal pleasure or safety, but to promote the interest of my country. These, therefore, I shall continue to pursue to the best of my judgment, and as to consequences, they are in the hand of God.”

Morris returned to the U.S. in 1798 and was elected to the Senate in 1800. He married in 1809 at the age of 57 and in 1816, at the age of 64, he died. Though he was the “Penman of the Constitution” and his philosophy honored the unique foundation of American government at the time, his most important legacy was his stand for truth in Paris on August 10, 1792. It demonstrated that there is an alternative to the extremes of tyranny and anarchy that plague the world. It is the rule of law based on our capacity for self-government. But this is only possible if we return to the Lord God as the source of our rights and utilize methods of change that glorify Him. Oh, how we need this truth today!