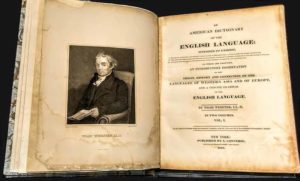

On April 14, 1828, Noah Webster, at the age of 70, had his long-awaited American Dictionary of the English Language copyrighted and ready for publication. The year before, when finishing the work, he wrote from Cambridge, England: “When I had come to the last word, I was seized with a trembling which made it somewhat difficult to hold my pen steady for writing. The cause seems to have been the thought that I might not then live to finish the work, or the thought that I was so near the end of my labors.”

On April 14, 1828, Noah Webster, at the age of 70, had his long-awaited American Dictionary of the English Language copyrighted and ready for publication. The year before, when finishing the work, he wrote from Cambridge, England: “When I had come to the last word, I was seized with a trembling which made it somewhat difficult to hold my pen steady for writing. The cause seems to have been the thought that I might not then live to finish the work, or the thought that I was so near the end of my labors.”

In 1806, Noah Webster first published A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language. It was the start of what would become his American Dictionary of the English Language. Webster’s original premise was: “As an independent nation, our honor requires us to have a system of our own, in language as well as government. Great Britain, whose children we are, and whose language we speak, should no longer be our standard; for the taste of her writers is already corrupted, and her language on the decline.” The journey to accomplish this goal of a distinctly American dictionary would involve mastering 26 languages, traveling twice to Europe, and over 22 years of study!

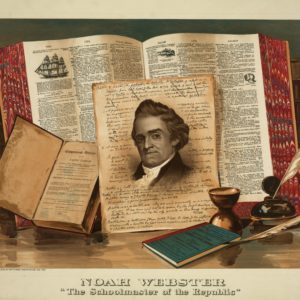

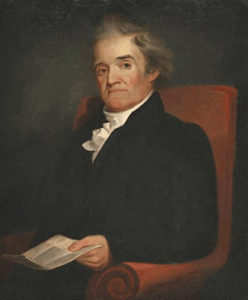

Noah Webster was born in West Hartford, Connecticut in 1758. He learned a solid work ethic from his parents through rising early, milking cows, plowing fields, and mending stone walls. He attended classes in a local log schoolhouse. In 1774, when sending his son to Yale College, he remarked, “Serve your generation and do good in the world.” No wonder his philosophy of education was that “all government originates in families, and if neglected there, it will hardly exist in society.” His marriage in 1709 to Rebecca Greenleaf, of French Huguenot descent, helped fulfill his own family’s calling.

Noah Webster never forgot the admonitions of his parents or the work ethic he learned at home. Consider a few of his productive works that blessed generations of Americans. His Blue-Backed Speller, published in 1783, became a best-seller, with 100 million copies rolling off the presses in 100 years! The 1794 edition included a catechism on the new U.S. Constititution. The 1784 Grammar and 1785 Reader raised a standard for parental teaching for decades. His “Sketches of American Policy,” a tract written in 1785 and delivered to Mount Vernon, instructed and inspired George Washington just in time before the Constitutional Convention took place in 1787.

Noah Webster never forgot the admonitions of his parents or the work ethic he learned at home. Consider a few of his productive works that blessed generations of Americans. His Blue-Backed Speller, published in 1783, became a best-seller, with 100 million copies rolling off the presses in 100 years! The 1794 edition included a catechism on the new U.S. Constititution. The 1784 Grammar and 1785 Reader raised a standard for parental teaching for decades. His “Sketches of American Policy,” a tract written in 1785 and delivered to Mount Vernon, instructed and inspired George Washington just in time before the Constitutional Convention took place in 1787.

Though Noah Webster had written consistently that the Christian religion “is the most important and one of the first things in which all children, under a free government, ought to be instructed,” he had not surrendered to Christ. In 1807, a revival in New Haven that affected his wife and two oldest daughters caught his attention. Soon he could not resist the conviction of his conscience and his full surrender was “soon followed by that peace of mind which the world can neither give nor take away.”

Webster was active in his community. At times he was a member of the General Assembly, a councilman, an alderman, and a judge, and he was also elected to the General Court. He founded Amherst Academy in 1816, served as selectman of Amherst, directed the Hampshire Bible Society, and served as Vice-President of the Hampshire and Hampden Agricultural Society. He didn’t just write about the fact that America’s religious and civil liberty were uniquely drawn from Christianity; he acted on these truths, doing what he could to preserve such values.

The philosophy behind his educational textbooks and the writing of his dictionary was that there were two forces that must be balanced at all times – universal undisputed practice and the principle of analogy. When new words or concepts are invented or developed, a nation’s vocabulary changes. However, the universal unity or national integrity must not change. Thus, both change and changelessness are what help to keep national unity through a national language. To declare no national language, as is the trend today, is to put a nation on a literary spin toward change that is out of control – it is anarchy.

The philosophy behind his educational textbooks and the writing of his dictionary was that there were two forces that must be balanced at all times – universal undisputed practice and the principle of analogy. When new words or concepts are invented or developed, a nation’s vocabulary changes. However, the universal unity or national integrity must not change. Thus, both change and changelessness are what help to keep national unity through a national language. To declare no national language, as is the trend today, is to put a nation on a literary spin toward change that is out of control – it is anarchy.

Consider two definitions that illustrate Webster’s use of Scripture and concepts like liberty under law:

Wisdom – The right use or exercise of knowledge (a biblical definition). In Scripture theology, wisdom is true religion; godliness; piety; the knowledge and fear of God, and sincere and uniform obedience to his commands. This is the wisdom which is from above. Psalms 90:12. Job 28:12.

Liberty – The liberty of men in a state of society, or natural liberty, so far only abridged and restrained, as is necessary and expedient for the safety and interest of the society, state or nation. A restraint of natural liberty, not necessary or expedient for the public, is tyranny or oppression… the restraints of law are essential to civil liberty. (In other words, true liberty is under law.)

Other concepts clearly articulated in his dictionary were the distinction between a republic and a democracy, as well as education, where he states in his definition: “To give them (children) a religious education is indispensable.” It is important to understand that those who can change the meaning of words (we call it equivocation) can subtly rule a nation. The dictionaries of today continue to change the meaning of words, unhinged by any Biblical, solid, or objective foundation. Webster wrote, “Almost all the civil liberty now enjoyed in the world owes its origin to the principles of the christian religion.”

Webster laid a sure foundation of the Bible as the root from which all words were defined; in other words, they had a solid meaning from which to reason. As Charles Wolfe, past President of the Plymouth Rock Foundation, wrote, “Webster was an amazing individual whose work and achievements can only be admired in our modern day. The productivity, strength of character, conviction of Biblical principle, and loyalty to home and hearth should give inspiration and hope to every American.”

Webster laid a sure foundation of the Bible as the root from which all words were defined; in other words, they had a solid meaning from which to reason. As Charles Wolfe, past President of the Plymouth Rock Foundation, wrote, “Webster was an amazing individual whose work and achievements can only be admired in our modern day. The productivity, strength of character, conviction of Biblical principle, and loyalty to home and hearth should give inspiration and hope to every American.”

The Introduction to his 1828 Dictionary includes the origin of language from Scripture and history, as well as an analysis of language in general and English in particular. The Preface concludes with this thought: “To that great and benevolent Being, who, during the preparation of this work, has sustained a feeble constitution, amidst obstacles and toils, disappointments, infirmities and depression; who has twice borne me and my manuscripts in safety across the Atlantic, and given me strength and resolution to bring the work to a close, I would present the tribute of my most grateful acknowledgments. And if the talent which he entrusted to my care, has not been put to the most profitable use in his service, I hope it has not been ‘kept laid up in a napkin,’ and that any misapplication of it may be graciously forgiven. – New Haven, 1828.” Let us restore the definition of words by returning to Webster’s 1828 Dictionary!