When people think of the historic Boston Tea Party that took place in 1773, they often have images of wild and lawless men destroying the personal property of others and throwing it into the sea in a riot, just so they don’t have to pay a very small tax. About the only thing that is accurate in this description of the event that took place on Thursday, December 16, 1773 is the fact that the proposed tax was small! It is time to rehearse the rest of the story, which is often left untold.

The colony of Massachusetts, like the other 12, had their own parliaments, some called Assemblies, or House of Burgesses like Virginia. In Massachusetts it was called the Council or General Court. Though the Charter of 1691 made Massachusetts a Royal Colony with appointed Governors and Lt. Governors, the Colony retained its legislative powers of self-government or “taxation with representation.” What united all the colonies was the national executive, the King and his representative Governors. However, there was no confusion as to the limitation of the English Parliament – they only directly governed citizens in England. The unalienable rights of Englishmen were clearly preserved in written law for the 13 colonies; only by consent through representatives, could they be taxed.

But what about an unjust tax? What if Parliament oversteps its bounds? English common law, or rule by precedent, had developed four steps to appeal unjust taxation. The major flaw in the English “constitution” was no written appeals system, but these four steps had become the accepted procedure long before 1773. These four steps were a) a civil vote to refuse the product due to the unjust tax and subsequently keeping the goods in port for at least 20 days (to give the owner a chance to leave and redeem the value of his cargo); b) the protection of the owner and his property (no one could steal the product or harm the owner of the ship); c) conduct a popular demonstration against the tax; and d) after twenty days, the product was liable for seizure or in other words, must be destroyed.

But what about an unjust tax? What if Parliament oversteps its bounds? English common law, or rule by precedent, had developed four steps to appeal unjust taxation. The major flaw in the English “constitution” was no written appeals system, but these four steps had become the accepted procedure long before 1773. These four steps were a) a civil vote to refuse the product due to the unjust tax and subsequently keeping the goods in port for at least 20 days (to give the owner a chance to leave and redeem the value of his cargo); b) the protection of the owner and his property (no one could steal the product or harm the owner of the ship); c) conduct a popular demonstration against the tax; and d) after twenty days, the product was liable for seizure or in other words, must be destroyed.

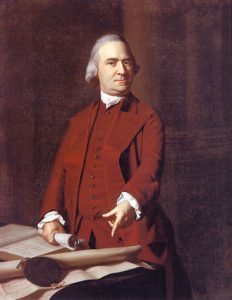

The oppression of the English Parliament began in earnest in 1761 with the Writs of Assistance. This was a law saying the British could search ships without a warrant. James Otis defended the colonial merchants of Boston for free. His oration, pictured in the Boston State House, declared clearly that rights were not in the crown, or property, or even ultimately in the compact between King and the people (constitution). Rights come from “the unchanging will of God.” The idea that rights are God-given and not government granted were spread from colony to colony through the Committees of Correspondence begun by Sam Adams in 1772.

When the Stamp Act and the other taxes were laid by Parliament, they appealed in writing that these were unconstitutional. They quoted their charters and stated the violation of their rights as Englishmen. When Parliament repealed the taxes on paper, painter’s colors and glass, only a small tax on tea remained to “try the principle in America.” They thought the colonists would “swallow” the principle since they could buy tea at a lower price than they could smuggle it from Holland. Ben Franklin stated “They have no idea that any people can act from any other principle but that of interest; and they believe that three pence on a pound of tea, of which one does not perhaps drink ten pounds in a year, is sufficient to overcome all the patriotism of an American.” A tax of 30 cents a year!

Patriots in Philadelphia got the Tea Commissioners (those who collect the internal tax) to resign. New York patriots voted that the tea should not land there. In Charleston, the consignees resigned to rounds of thunderous applause for their patriotism. In Boston, the Selectmen voted unanimously not to land the tea, but the Consignees refused to resign, and the Governor refused to allow the ship laden with tea to return to England. All eyes were on Boston. As one Philadelphia letter stated, “All we fear is that you will shrink at Boston. May God give you virtue enough to save the liberties of your country.”

The British knew the common law. They threatened to forcefully unload the tea on December 17, the 21st day after the first ship had arrived November 28. When Sam Adams convened a meeting on the exact hour twenty days after the first ship had arrived, he received word that the owner would not be allowed to leave with his cargo. Some unrest began to occur, but Adams, as well as other leaders, told the people the owner had done nothing wrong – he was to be protected as well as his ship. Then he said, “This meeting can do nothing more to save the country.” With that, the war hoop was sounded, and the action began. A lawful strategy of interposition, or resisting an unjust tax through already established means was planned or simple statements would remain fruitless.

The British knew the common law. They threatened to forcefully unload the tea on December 17, the 21st day after the first ship had arrived November 28. When Sam Adams convened a meeting on the exact hour twenty days after the first ship had arrived, he received word that the owner would not be allowed to leave with his cargo. Some unrest began to occur, but Adams, as well as other leaders, told the people the owner had done nothing wrong – he was to be protected as well as his ship. Then he said, “This meeting can do nothing more to save the country.” With that, the war hoop was sounded, and the action began. A lawful strategy of interposition, or resisting an unjust tax through already established means was planned or simple statements would remain fruitless.

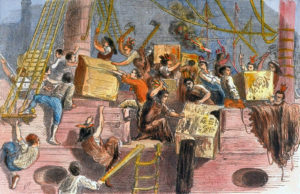

This is when about 60 men, some disguised as Mohawk Indians, gave a war hoop as they went to the wharf and unloaded 9,000 pounds of tea in 342 chests. No property was damaged, no one was hurt, and hardly any sound was made. The tea was liable for seizure and anyone caught stealing tea was fined. Governor Hutchinson (the Tory who refused the allow the ship to leave), said, “The whole was done with very little tumult.” Sam Adams called it the “height of joy.” John Adams said, “This is the most magnificent movement of all.” John Scollay, a selectmen from the town of Boston who had voted for the act, said, “We do console ourselves that we have acted constitutionally.” After all, they had followed every step of the common law for a lawful boycott of goods unjustly taxed!

This is when about 60 men, some disguised as Mohawk Indians, gave a war hoop as they went to the wharf and unloaded 9,000 pounds of tea in 342 chests. No property was damaged, no one was hurt, and hardly any sound was made. The tea was liable for seizure and anyone caught stealing tea was fined. Governor Hutchinson (the Tory who refused the allow the ship to leave), said, “The whole was done with very little tumult.” Sam Adams called it the “height of joy.” John Adams said, “This is the most magnificent movement of all.” John Scollay, a selectmen from the town of Boston who had voted for the act, said, “We do console ourselves that we have acted constitutionally.” After all, they had followed every step of the common law for a lawful boycott of goods unjustly taxed!

So what can we learn from the original Boston Tea Party? First, we must restore an understanding of constitutional due process today, so we can discern when we are ignoring the rule of law. Second, we need to learn to communicate with our legislators and fellow Americans in such a way as to bring agreement to resist arbitrary acts of government through interposition (lawful and peaceful resistance). Third, and most important, at this time of year, we should be blessed than the coming of Christ was in the fullness of time and “under law” (Galatians 4:4). Christ’s birth as the God-man was not arbitrary, but according to the due process to atone for sin.

Joseph Warren, who led the original Tea Party, stated, “On you depend the fortunes of America…. you must have the strongest confidence that the same Almighty Being who protected your pious and venerable forefathers… (will) preside in all our councils… may… direct us to such measures as He himself shall approve, and be pleased to bless…. May our land be a land of liberty, the seat of virtue, the asylum of the oppressed, a name and a praise in the whole earth.”