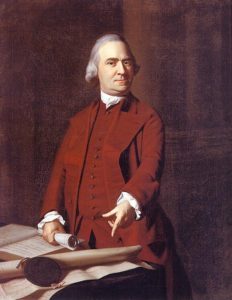

After probably pondering the idea for weeks, on Monday, November 2, 1772, at a Town Meeting in Faneuil Hall (Boston), Sam Adams proposed “that a committee of correspondence be appointed, to consist of twenty-one persons, to state the rights of the colonies, and of this province in particular, as men, as Christians, and as subjects; to communicate and publish the same to the several towns in this province and to the world, as the sense of this town, with the infringements and violations thereof that have been, or from time to time may be, made; also requesting of each town a free communication of their sentiments on this subject.” Although initially opposed by some patriots, his motion passed and it “multiplied and widened under successive impulses, until they constituted the accredited organs of the party that founded the Republic of the United States.”

After probably pondering the idea for weeks, on Monday, November 2, 1772, at a Town Meeting in Faneuil Hall (Boston), Sam Adams proposed “that a committee of correspondence be appointed, to consist of twenty-one persons, to state the rights of the colonies, and of this province in particular, as men, as Christians, and as subjects; to communicate and publish the same to the several towns in this province and to the world, as the sense of this town, with the infringements and violations thereof that have been, or from time to time may be, made; also requesting of each town a free communication of their sentiments on this subject.” Although initially opposed by some patriots, his motion passed and it “multiplied and widened under successive impulses, until they constituted the accredited organs of the party that founded the Republic of the United States.”

There had been attempts to unify the colonies on the basis of their rights prior to 1772. From the New England Confederacy of 1643 to Ben Franklin’s Albany Plan of 1754, none of the attempts were successful since they either lacked enough unity or were so centralized that colonies felt their liberty was not respected. Three aspects of the principle of covenant, derived from the Bible and communicated through these committees, would resolve the problem. First, they would emphasize that all should be under one law (or constitution). Second, their unity would be built on self-government and self-preservation. Third, their union would respect jurisdiction, or the liberty of each colony to govern its own affairs without interference as expressly written in any constitutional document.

Samuel Adams’ treatise in 1772 stated the principles that united them as men, Christians, and subjects of England and its constitution. Joseph Warren then articulated the violations of those liberties. Finally, Benjamin Church invited the town to which the letter came to communicate with Boston and other cities and colonies so the people and leaders could be united in root ideas worth defending. Adams began with these words, “Among the natural rights of the Colonists are these: First, a right to life; Secondly, to liberty; Thirdly, to property; together with the right to support and defend them in the best manner they can. These are evident branches of, rather than deductions from, the duty of self-preservation, commonly called the first law of nature.”

Samuel Adams’ treatise in 1772 stated the principles that united them as men, Christians, and subjects of England and its constitution. Joseph Warren then articulated the violations of those liberties. Finally, Benjamin Church invited the town to which the letter came to communicate with Boston and other cities and colonies so the people and leaders could be united in root ideas worth defending. Adams began with these words, “Among the natural rights of the Colonists are these: First, a right to life; Secondly, to liberty; Thirdly, to property; together with the right to support and defend them in the best manner they can. These are evident branches of, rather than deductions from, the duty of self-preservation, commonly called the first law of nature.”

He then went on to write a very key point: “When men enter into society, it is by voluntary consent; and they have a right to demand and insist upon the performance of such conditions and previous limitations as form an equitable original compact. Every natural right not expressly given up, or, from the nature of a social compact, necessarily ceded, remains.” Life, liberty, and property are essential unalienable rights given by God, and thus a certain “toleration” is due to all. These are their rights as “men” or creations of God (male and female).

He then stated that “as Christians” our rights “may be best understood by reading and carefully studying the institutes of the great Law Giver and Head of the Christian Church, which are to be found clearly written and promulgated in the New Testament.” This means that each individual has a “natural right to worship God according to the dictates of his own conscience.”

He then stated that “as Christians” our rights “may be best understood by reading and carefully studying the institutes of the great Law Giver and Head of the Christian Church, which are to be found clearly written and promulgated in the New Testament.” This means that each individual has a “natural right to worship God according to the dictates of his own conscience.”

Finally, he stated the “rights as subjects” of England: “All persons born in the British colonies are, by the laws of God and nature and by the common law of England, exclusive of all charters from the Crown, well entitled, and by acts of the British Parliament are declared to be entitled to all the natural, essential, inherent, and inseparable rights, liberties, and privileges of subjects born in Great Britain or within the realm.”

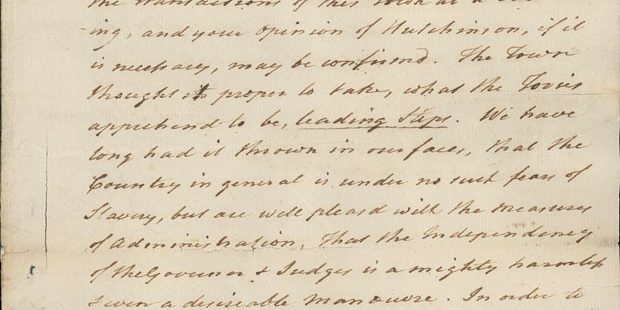

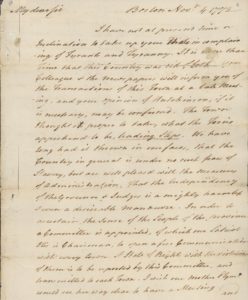

With such clarity of God-given rights and self-preservation asserted (having their own mini parliaments), most colonies had heard such sentiments for decades in their churches and thus would respond in unity. The letter was sent to 250 cities and towns. In four weeks, 45 had responded, and in five weeks, 80! But which town was first? Who would spark such a grass-roots effort? Why, Plymouth, of course! Sam Adams wrote to his good friend, James Warren of Plymouth: “I have not at present time or inclination to take up your thots in complaining of Tyrants and Tyranny. It is more than time that this Country was rid of both.” After reiterating that each town is to state its sense of rights, he writes, “I wish our Mother Plymouth would see her way clear to have a meeting and second Boston by appointing a Committee of Communication and Correspondence.” No wonder such a legacy of liberty would come from the town the Pilgrims founded!

James Warren of Plymouth was married to Mercy Otis. Though James was a member of the General Court, the Provincial Congress, and the Massachusetts Militia, his wife was an articulate historian of the Revolution. Her dramas and historical volumes were published in 1805. Her statue in Barnstable forever demonstrates that the power of the written word can change hearts and history!

James Warren of Plymouth was married to Mercy Otis. Though James was a member of the General Court, the Provincial Congress, and the Massachusetts Militia, his wife was an articulate historian of the Revolution. Her dramas and historical volumes were published in 1805. Her statue in Barnstable forever demonstrates that the power of the written word can change hearts and history!

The first town to respond was in Massachusetts. The first colony to respond was Virginia. The first county was in New Jersey. And in 1774, New York suggested that they all unite in a Continental Congress. This was the bottom-up unity that produced the “lower magistrate,” duly elected, that had authority to resist the top-down tyrannical measures of the Crown. As Dr. Collins observed, “…it was correspondence, with cooperation at the terminal points, that brought about the Revolution… It was not merely a channel through which public opinion might flow; it created public opinion and played upon it to fashion events… these committees, local and inter-colonial… were the germ of a government.”

The lessons learned from this virtually unknown, bottom-up groundswell that produced a lawful resistance to tyranny (so that the American Revolution ended in more liberty when most revolutions end in more tyranny) ought to be clear. Today, we have a greater avenue of communication through the internet than our forebears could ever have conceived. However, we often lack the understanding of the fundamental principles of covenant and God-given rights, or the fortitude of initiating a communication of these in a winsome and creative way.

We must also remember that a compassion to help people, with great need ever before us, must be balanced with a principled direction. The goal is that individuals assume a greater measure of self-government and self-preservation so that they might live with greater integrity and the blessing of being independent!