Remember the one who fell overboard from the Mayflower? John Howland, the young man whose life was almost snuffed out in 1620, is John Howland the man in 1634 – in command of a post 170 miles north of Plymouth, refereeing a political dispute, driving away a threat to Plymouth’s wellbeing, and coming out of the incident with honor, having defended a just cause.

Remember the one who fell overboard from the Mayflower? John Howland, the young man whose life was almost snuffed out in 1620, is John Howland the man in 1634 – in command of a post 170 miles north of Plymouth, refereeing a political dispute, driving away a threat to Plymouth’s wellbeing, and coming out of the incident with honor, having defended a just cause.

To trace the steps that led from the boy to the man, from the fledgling band huddled in a ship to the well-established, internationally and economically viable colony, we must go back to the very root. Most of us know quite well the ecclesiastical history of the Mayflower Pilgrims, as they are known today. They had their origins in the congregation that clustered around Scrooby, England. As Separatists, they were unwelcome in the Church of England parishes because they represented a challenge to the authority of the bishop and ultimately a challenge to the king’s authority over the church also.

Their desire for obedience to the Scripture brought them to a conviction that they must leave England and its enforcement of unbiblical practices of worship, and must seek refuge in the Lowlands where they might enjoy religious liberty. In Amsterdam and later in Leyden, they did find religious liberty. But there they were threatened by a new cultural force. The worldliness of the Dutch who had lived too long under a loose form of toleration began to draw away the Pilgrim children to carnal lifestyles. For the welfare of their children, the Separatists in Leyden decided upon a journey to the northern parts of Virginia (as detailed in William Bradford’s Of Plimoth Plantation).

But there were huge financial hurdles that had to be overcome for the congregation to survive and to achieve that liberty to follow Scripture that the men and women we call Pilgrims so dearly cherished and so earnestly sought. This part of their history is less known. To understand their political and economic situation, let us lay a little historical groundwork. There were two companies authorized by the English crown to colonize the New World. The company authorized to settle toward the south was called the Virginia Company of London; it was given responsibility to colonize all land between the latitudes of 34° N and 41° N. The company authorized to settle toward the north was called the Virginia Company of Plymouth and Bristol; it was given responsibility to colonize all land between the latitudes of 38° N and 45° N, overlapping some with the Virginia Company of London.

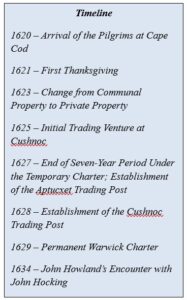

By 1620, both authorized companies were struggling to attract colonizers. So they resorted to a new scheme approved by the crown, that of establishing what were known as “particular plantations.” This scheme allowed that private investors could obtain a temporary charter from one of the two companies, establish a colony within that company’s borders, and see if the colony could survive for seven years, after which time the investors could apply for a permanent charter for a specific amount of land based on the number of adults living in the colony.

It was this opportunity that the Merchant Adventurers, the group of private investors with whom the Pilgrims had become acquainted, capitalized upon in 1620. They obtained a temporary charter from the company in charge of the southern lands, the Virginia Company of London, authorizing the Pilgrims to establish a “particular plantation” anywhere between the latitudes of 34° N and 41° N.

After a difficult departure, fraught with delays and setbacks, the Pilgrims set out on the voyage. Blown off course to the north, after two months at sea, they made landfall at Cape Cod, 65 miles north of the 41st parallel, thus 65 miles outside of the territory in which their patent would have been valid. With winter already descending upon the continent, given the time of year and the need to disembark and erect shelters quickly, the Pilgrims took it as Providence that they were to settle here in Cape Cod.

After a difficult departure, fraught with delays and setbacks, the Pilgrims set out on the voyage. Blown off course to the north, after two months at sea, they made landfall at Cape Cod, 65 miles north of the 41st parallel, thus 65 miles outside of the territory in which their patent would have been valid. With winter already descending upon the continent, given the time of year and the need to disembark and erect shelters quickly, the Pilgrims took it as Providence that they were to settle here in Cape Cod.

Now several steps had to be taken to legalize their situation. First, they drew up the Mayflower Compact as an immediate measure to unite themselves politically, in covenant with one another before God – just as they had done to unite themselves ecclesiastically in drawing up their church covenant in Scrooby. Next, they had to obtain a new temporary charter to establish their “particular plantation,” this time within the bounds of the company responsible for northern colonization rather than southern. (By this time, the northern company was called the Council for New England, which had succeeded the Virginia Company of Plymouth and Bristol.) Once this charter could be obtained, they then had to survive for seven years before they could have a permanent charter and true property ownership.

All of this required several trips made by representatives and negotiators back and forth across the water. While these matters were being negotiated, the Mayflower Compact, the only covenant and law code they had for some time, held strong and was useful in the good ordering of their society. But to succeed as a colony for seven years and beyond, they must have a means of productivity and trade. And in Cape Cod, there was no immediate prospect of lucrative trade. It became apparent that they would have difficulty surviving for seven years, paying off the debt they owed to the Merchant Adventurers, and establishing themselves as a permanent colony.

As was their custom, they sought the Lord in this extremity. By His grace, they were sustained through an extremely harsh winter and severe economic setbacks. But even after the famous First Thanksgiving, they by no means “had it made,” as is commonly misconceived. In fact, those years following the First Thanksgiving were some of the most difficult years for Plymouth Colony. New ships arrived, bringing hungry mouths to feed and no provisions. Drought befell them. The system of communal property and responsibility, in which everyone received equal benefit regardless of the amount of labor he invested, had the colony on the brink of starvation and disaster.

In these most desperate times, the Pilgrims held a day of fasting and prayer. They sought the Lord, and He heard their cries. He sent rain. He was faithful and daily met their needs. They changed their system from one of communal property to one of private property. Though they did not yet truly own the land, they began to divide it into family parcels, with each family responsible for growing their own food.

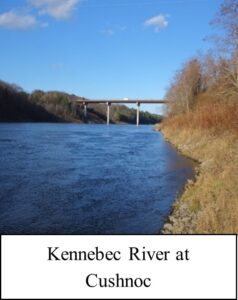

All of this was helpful, but not enough volume to bring the magnitude of financial return that the Pilgrims needed because they not only had to provide for their families, but also to satisfy their obligation to the Merchant Adventurers. Their faithful God again met their needs, and in His providence, He opened another door, the door that would prove key for them in turning the colony around from a financial sinkhole to a productive and viable entity. In 1625, some of the Pilgrims ventured 170 miles north. What was the attraction? Only five years after landing, being scarcely established, why venture so far north? There, near present-day Augusta, Maine, lies the Kennebec River. Here the Pilgrims saw an opportunity for trade unlike any they could find in their own Cape Cod. For along the river lived countless beavers – an extremely desirable commodity for hatmakers back in Europe.

The Pilgrims learned of the vast beaver population and came on a one-time trading mission to investigate the possibility for further trade. This initial venture of trading with the Natives for beaver pelts proved quite profitable, so they returned home to Plymouth and began to lay plans for establishing a more permanent trading post in the area. If they could erect such a post and begin to tap into the large population of Native Americans eager to buy European items . . . it could be a golden opportunity!

As they worked at this plan, two years later, in 1627, their seven years expired, and by God’s kind hand, they had survived. But they were far from being well-established economically. They still owed £1800 to the Merchant Adventurers. At this point, eight of the leading men of the colony stepped forward to take upon their own shoulders the financial responsibility of paying back the Merchant Adventurers, lifting the burden off the rest of the colony. Eight men known as “Undertakers” – William Bradford, Myles Standish, Isaac Allerton, Edward Winslow, John Howland, John Alden, William Brewster, and Thomas Prence – undertook to pay off the debt. They agreed to pay £200 each year until the total £1800 was paid off. This was projected to take them until 1636.

In order to follow this course of action, they knew that they must continue their efforts to establish more profitable trade. That very year, 1627, they accordingly established a smaller trading post at Aptucxet on Cape Cod. Here, they traded for furs from the Natives in exchange for beads (valued by the Natives for jewelry and as a medium of exchange). The furs they then traded with the French and the Dutch for money, more beads, and other goods.

In order to follow this course of action, they knew that they must continue their efforts to establish more profitable trade. That very year, 1627, they accordingly established a smaller trading post at Aptucxet on Cape Cod. Here, they traded for furs from the Natives in exchange for beads (valued by the Natives for jewelry and as a medium of exchange). The furs they then traded with the French and the Dutch for money, more beads, and other goods.

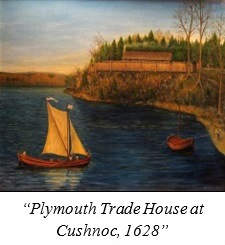

The next year, in 1628, the Pilgrims finished the plans they had begun in 1625, planting their trading post on the Kennebec River. The name of the place they settled upon is “Cushnoc.” It means “where the current overpowers the tide” – for it is the northernmost limit of the tidewater in the Kennebec River. It would become a symbolic name as well. Here, the Pilgrims established their second and most productive trading post. At first, the trade was basic and primitive; beads and tools were desirable commodities amongst the Natives. The Pilgrims traded with the local tribes for furs. They then sold these furs on the European market. By the small current of this trade relationship, they hoped to soon overpower the rising tide of debt and pay it off to the Merchant Adventurers.

God blessed their efforts, and the year 1629 was an important year for Plymouth Colony. In this year, they finally obtained their permanent charter, signed by the Earl of Warwick and known as the Warwick Charter. The seven years complete, all the requirements for permanent colonization and land ownership were fulfilled. All that remained was to pay off their debt to the Merchant Adventurers. It is revealing of the importance of this trading post along the Kennebec that the Warwick Charter granted not only the due allotment of land in Plymouth, but also the relatively large swath of land at Cushnoc along the Kennebec, running about 20 miles along the river and 30 miles wide, 15 miles on either side of the river. As part of the charter, the Pilgrims were granted a monopoly on beaver furs within this section of land.

God blessed their efforts, and the year 1629 was an important year for Plymouth Colony. In this year, they finally obtained their permanent charter, signed by the Earl of Warwick and known as the Warwick Charter. The seven years complete, all the requirements for permanent colonization and land ownership were fulfilled. All that remained was to pay off their debt to the Merchant Adventurers. It is revealing of the importance of this trading post along the Kennebec that the Warwick Charter granted not only the due allotment of land in Plymouth, but also the relatively large swath of land at Cushnoc along the Kennebec, running about 20 miles along the river and 30 miles wide, 15 miles on either side of the river. As part of the charter, the Pilgrims were granted a monopoly on beaver furs within this section of land.

But trouble seems to rise up and threaten wherever God is working. Not long into the venture, the French and the Dutch encroached upon this patent and the monopoly, degrading the profitability for which the Pilgrims had hoped. Privateers also nibbled away at profits by stealing trade goods in the open waters. Isaac Allerton, a Pilgrim who was responsible for obtaining trade goods in England, mingled his own personal business with that of the Pilgrim trade goods, further diminishing their opportunities for success.

Wherever there is profit to be gained, there is a potential for strife. Such were the early days at Cushnoc. Blood was spilled on all sides in the early years. It is here that we find John Howland, the youth become a man, rising above petty squabbles and defending the precious treasure entrusted to his care. By 1634, he had become commander of the trading post at Cushnoc. And it was during his leadership that the trading post came under its greatest threat. A ship commander named John Hocking, from Portsmouth, England, sailed boldly into the Kennebec and toward the trading post. When he reached Cushnoc, John Howland ordered him to leave, asserting the Pilgrims’ crown-given monopoly on the trade in the region. But John Hocking ignored the warning and proceeded onward. Howland then set sail himself, along with John Alden, and caught up with Hocking and again ordered him to leave. When Hocking again refused, Howland ordered some of his men to sever Hocking’s anchor cables. As they began the work, Hocking shot and killed one of Howland’s men, Moses Talbot. The men then opened fire on Hocking and fatally wounded him.

Wherever there is profit to be gained, there is a potential for strife. Such were the early days at Cushnoc. Blood was spilled on all sides in the early years. It is here that we find John Howland, the youth become a man, rising above petty squabbles and defending the precious treasure entrusted to his care. By 1634, he had become commander of the trading post at Cushnoc. And it was during his leadership that the trading post came under its greatest threat. A ship commander named John Hocking, from Portsmouth, England, sailed boldly into the Kennebec and toward the trading post. When he reached Cushnoc, John Howland ordered him to leave, asserting the Pilgrims’ crown-given monopoly on the trade in the region. But John Hocking ignored the warning and proceeded onward. Howland then set sail himself, along with John Alden, and caught up with Hocking and again ordered him to leave. When Hocking again refused, Howland ordered some of his men to sever Hocking’s anchor cables. As they began the work, Hocking shot and killed one of Howland’s men, Moses Talbot. The men then opened fire on Hocking and fatally wounded him.

The case as to who was in the right swirled in the courts both of Plymouth and of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, which colony had been established four years earlier in 1630. After full investigation, Howland, Alden, and the Cushnoc trading post were fully exonerated, it being determined that they were lawfully upholding and defending their legal monopoly.

These were the glory days of the trading post. It was at its peak productivity, and by 1641, five years behind schedule, but finally producing a regular income thanks to Cushnoc, the Pilgrims gratefully were able to make their last payment to the Merchant Adventurers and were free to seek profits for themselves in earnest. By God’s power, the current of trade had overcome the tide of debt.

This trading post continued to produce for another decade or so, but with signs of decline. In 1654, the new governor of Plymouth, Thomas Prence, visited Cushnoc to secure loyalty from the local inhabitants. But these efforts amounted to but little, and in the next decade, the land was sold, and it was eventually absorbed into the Massachusetts Bay Colony, having served its purpose well and been God’s remarkable means for meeting the financial needs of the Pilgrims.

This trading post continued to produce for another decade or so, but with signs of decline. In 1654, the new governor of Plymouth, Thomas Prence, visited Cushnoc to secure loyalty from the local inhabitants. But these efforts amounted to but little, and in the next decade, the land was sold, and it was eventually absorbed into the Massachusetts Bay Colony, having served its purpose well and been God’s remarkable means for meeting the financial needs of the Pilgrims.

As in all trade adventures there were winners and losers, and these do not always identify themselves immediately. John Howland is worthy of commendation for his keen perception and for his decisive action to spare the young Plymouth Colony and to spare the trading post that God had raised up to sustain His little flock.

As the Pilgrims trusted God for provision and sustenance quite literally, so we must do likewise. Though our material needs may not be as apparent nor as dire as theirs on the surface, yet our lives always hang by a very slender thread. Just as God was able to raise up a trading post 170 miles to the north of the Pilgrims and thereby meet their need, so He is able to raise up help for us from the most unlikely sources and to do for us “exceeding, abundantly, above” all that we ask or think as we look to Him (Ephesians 3:20).

The Pilgrims worshiped by singing the Psalms, so they expressed their praise and gratitude in the language of the Psalms. One that William Bradford quoted and one that is very fitting for this occasion is Psalm 107. Let us join them in confessing the goodness of such a God, in the very words of their Psalter:

They in the wilderness in desert way wandered: no dwelling city find did they.

Hungry and thirsty eke [also]: that them within their soul, hath fainting overwhelméd been.

And to the LORD they cried in their distress: he freely rid them from their anguishes.

And in a right way he did make them go: a dwelling city for to come unto.

Confess they to Jehovah his mercy: his marvels eke [also], to sons of man earthly.

For he the thirsty soul hath satiated: and hungry soul with good replenishéd.

_________________________________

(1) Mary Huffman and her father, Gary, wrote this article after visiting Cushnoc during the summer. Mary has re-published the Ainsworth Psalter, available at www.plymrock.org.