The year was 1862. The bloody seven-day battle at Harrison Landing, also called the Peninsular Campaign in Virginia, had just concluded.

General Daniel Butterfield had lost 600 men and was wounded himself. He thought that the traditional bugle call to mark the end of the day, known as “Lights Out,” was too formal and not reverent enough to honor those who had died. He wanted it changed.

Oliver Wilcox Norton, his bugler, was called. He tells the story in his own words:

“…showing me some notes on a staff written in pencil on the back of an envelope, (he) asked me to sound them on my bugle. I did this several times, playing the music as written. He changed it somewhat… after getting it to his satisfaction, he directed me to sound that call for Taps thereafter in place of the regulation call.  The music was beautiful on that still summer night and was heard far beyond the limits of our Brigade. The next day I was visited by several buglers from neighboring Brigades, asking for copies of the music which I gladly furnished. The call was gradually taken up through the Army of the Potomac.”

The music was beautiful on that still summer night and was heard far beyond the limits of our Brigade. The next day I was visited by several buglers from neighboring Brigades, asking for copies of the music which I gladly furnished. The call was gradually taken up through the Army of the Potomac.”

Called “Scott Tattoo”, “Taps” replaced the combined French “Extinguish Lights” and the British “Last Post.” Tattoo was sounded to close a soldier’s day in the mid-1800s.

Both Union and Confederate troops eventually used “Taps”, and in 1874 it was officially recognized by the U.S. Army. It became standard at military funerals in 1891.Master Sergeant Jari A. Villanueva, holding Norton’s original bugle, describes “Taps” in this way:

Both Union and Confederate troops eventually used “Taps”, and in 1874 it was officially recognized by the U.S. Army. It became standard at military funerals in 1891.Master Sergeant Jari A. Villanueva, holding Norton’s original bugle, describes “Taps” in this way:

“There is something singularly beautiful and appropriate in the music of this wonderful call. Its strains are melancholy, yet full of rest and peace. Its echoes linger in the heart long after its tones have ceased to vibrate in the air… of all the military bugle calls, none is so easily recognized or more apt to render emotion than the call Taps….”

Col. James A. Moss’ Officer’s Manual describes the first use of “Taps” at a funeral:

Col. James A. Moss’ Officer’s Manual describes the first use of “Taps” at a funeral:

During the Peninsular Campaign of 1862, a soldier of Tidball’s Battery A of the 2nd Artillery was buried at a time when the battery occupied an advanced position concealed in the woods. It was unsafe to fire the customary three volleys over the grave, on account of the proximity of the enemy, and it occurred to Captain Tidball that the sounding of Taps would be the most appropriate ceremony that could be substituted.

The first sounding of “Taps” at a military funeral is commemorated in a stained glass window at The Chapel of the Centurion (The Old Post Chapel) at Fort Monroe, Virginia. The window, made by R. Geissler and based on a painting by Sidney King, was dedicated in 1958 and shows a bugler and a flag at half staff.

The site where “Taps” was born is also commemorated by a monument at Berkley Plantation, Virginia. It was erected by the Virginia American Legion and dedicated July 4, 1969. Rich in history, the site of Berkley Plantation is where Virginia’s first Thanksgiving took place in 1619. The original Harrisons of Berkley included Benjamin Harrison and William Henry Harrison, both presidents of the United States. Its legacy also includes Benjamin Harrison (father and great grandfather of these Presidents), who signed the Declaration of Independence.

The site where “Taps” was born is also commemorated by a monument at Berkley Plantation, Virginia. It was erected by the Virginia American Legion and dedicated July 4, 1969. Rich in history, the site of Berkley Plantation is where Virginia’s first Thanksgiving took place in 1619. The original Harrisons of Berkley included Benjamin Harrison and William Henry Harrison, both presidents of the United States. Its legacy also includes Benjamin Harrison (father and great grandfather of these Presidents), who signed the Declaration of Independence.

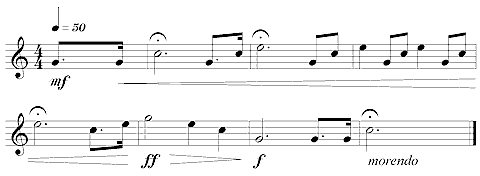

In its history, it is evident that “Taps” is born from the reverent belief that life is a gift of God, and those who give the ultimate sacrifice are to be remembered as imitating the sacrifice of our Lord on the cross. As soon as the song “Taps” was created, words were put to the music. The following verses have become familiar. The 24 mournful notes commemorate the memory of those who served in  all five branches of the military. May we honor all those who have given their lives to preserve our liberty as we reflect on the reverent melody of “Taps:”

all five branches of the military. May we honor all those who have given their lives to preserve our liberty as we reflect on the reverent melody of “Taps:”

“Day is done, gone the sun, from the hills, from the lake, from the sky. All is well, safely rest, God is nigh.

Go to sleep, peaceful sleep, may the soldier or sailor, God keep. On the land or the deep, safe in sleep.

Thanks and praise, for our days, ‘neath the sun, neath the stars, ‘neath the sky, as we go, this we know, God is nigh.”

1st Thessalonians 5:18 reads: “In everything give thanks; for this is the will of God in Christ Jesus for you.” In reverence, as we commemorate Thanksgiving this year, let us also pause and remember those who gave the ultimate sacrifice that we might be free. Let us pray for the families of those who have lost loved ones in their defense of our liberty.

1st Thessalonians 5:18 reads: “In everything give thanks; for this is the will of God in Christ Jesus for you.” In reverence, as we commemorate Thanksgiving this year, let us also pause and remember those who gave the ultimate sacrifice that we might be free. Let us pray for the families of those who have lost loved ones in their defense of our liberty.

Freedom isn’t free, and the need to defend our liberty is increasingly recognized in the day in which we live. May God grant that each of us will cherish the liberties that God has given us in our nation, for “Blessed is the nation whose God is the Lord” (Psalm 33:12).