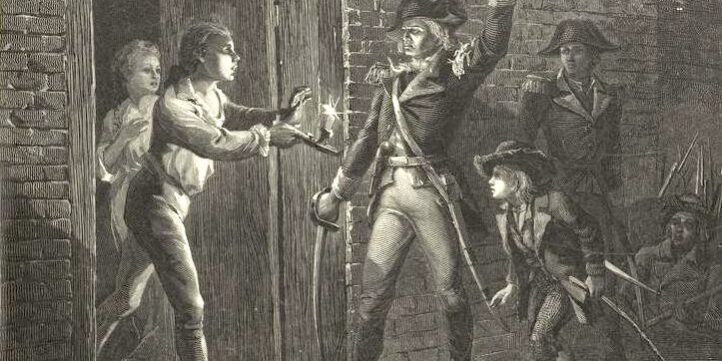

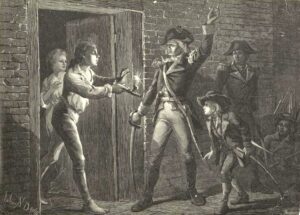

On Wednesday, May 10, 1775, at about sunrise, Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold pounded on the door of the British commander of Fort Ticonderoga. When opened, Allen demanded that the fort be surrendered. When asked by what authority, Allen responded, “In the name of the Great Jehovah and the Continental Congress!”

On Wednesday, May 10, 1775, at about sunrise, Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold pounded on the door of the British commander of Fort Ticonderoga. When opened, Allen demanded that the fort be surrendered. When asked by what authority, Allen responded, “In the name of the Great Jehovah and the Continental Congress!”

The British at Fort Ticonderoga and Crown Point did not know about the battles of Lexington and Concord, and thus were unaware war had begun. With only 50 soldiers manning the fort, the British surrendered immediately to the superior forces.

Following Lexington and Concord, the British had laid siege to Boston, thinking the rest of the other 12 colonies would abandon her and thus she would be starved into submission. Instead, inspired by prayer and fasting, the preaching of the clergy, and the Committees of Correspondence, the colonies were deeply united and smuggled supplies into Boston from the countryside.

Local militias surrounded the British. However, the militias had no way of getting the British to leave, for they had no cannon or artillery. In March of 1775, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress sent John Brown, with his guide, Peleg Sunderland, into Canada. They specifically spied on Fort Ticonderoga, saw it was sparsely defended, and recommended it be taken for the 80 pieces of cannon and artillery available there.

In 1755, the French had built Fort Carillon, offering access to Canada and the Hudson River Valley. The French and Indian War brought more fighting at this fort than anywhere else. In July of 1758, the British were defeated in the Battle of Carillon. However, they returned the next year and defeated the French, driving them north to Canada, and renaming Fort Carillon as Fort Ticonderoga. The word “Ticonderoga” is derived from an Iroquois word meaning “between two waters.”

Ethan Allen was born in 1738 in Connecticut, bought property in the “New Hampshire Grants” (later called Vermont in 1757), and fought in the French and Indian War. In 1770, he became the leader of the Green Mountain Boys, a militia group who arose in defense of their property rights because of the Albany Ejectment Trials in New York, which had stripped them of ownership. Allen represented the landowners in the trial. In 1775, Connecticut hired Allen and the Green Mountain Boys to attack Fort Ticonderoga to capture the cannons and heavy artillery.

Ethan Allen was born in 1738 in Connecticut, bought property in the “New Hampshire Grants” (later called Vermont in 1757), and fought in the French and Indian War. In 1770, he became the leader of the Green Mountain Boys, a militia group who arose in defense of their property rights because of the Albany Ejectment Trials in New York, which had stripped them of ownership. Allen represented the landowners in the trial. In 1775, Connecticut hired Allen and the Green Mountain Boys to attack Fort Ticonderoga to capture the cannons and heavy artillery.

Shortly before the planned raid, Benedict Arnold and his men arrived and wanted to take over the leadership of the attack. The Green Mountain Boys only laughed at such a suggestion. Arnold and Allen argued about who had superior authority. With a total of about 200 to 300 men, Allen (with Arnold on his left side) entered Ticonderoga, finding the gate unlocked and only one British regular, whom they quickly overpowered. Allen and his men shouted three “huzzahs,” awakening the garrison. Allen deflected an attack by a sentry and demanded to be led to the commandant’s headquarters. According to Ethan Allen, he and Arnold demanded the surrender of Ticonderoga “in the name of the Great Jehovah and the Continental Congress.”

What is interesting to note is that the colony of Connecticut commissioned Ethan Allen and his men, and the Provincial Congress of Massachusetts commissioned Benedict Arnold and his men. Both Allen and Arnold wanted credit for capturing the fort and securing America’s first victory, as did Connecticut and Massachusetts. Announcing the authority of the “Continental Congress” was an interesting foresight of unity that rose above the egos of the two leaders.

What is interesting to note is that the colony of Connecticut commissioned Ethan Allen and his men, and the Provincial Congress of Massachusetts commissioned Benedict Arnold and his men. Both Allen and Arnold wanted credit for capturing the fort and securing America’s first victory, as did Connecticut and Massachusetts. Announcing the authority of the “Continental Congress” was an interesting foresight of unity that rose above the egos of the two leaders.

As for demanding the fort surrender “in the name of the Great Jehovah,” this was a testament to the prevailing view of the time, for neither Arnold nor Allen personally professed or practiced such devotion to the God of the Bible.

Ethan Allen was a Revolutionary War hero, but his ego and longing for credit has brought him criticism – and for good reason. He wrote in 1785, “Being conscious I am no Christian” as a part of the preface to the book he published called Reason: The Only Oracle of Man. Like Thomas Paine and others, his criticism of Christianity and the Bible as being myths caused his book to be a failure. But God still used him at a critical time, that His higher purpose of liberty as an expression of His Kingdom might be achieved. God has always used flawed, and at times detrimental, characters for His purposes.

Benedict Arnold is known as the traitor of America’s cause. This notoriety stained every positive attribute and heroism he exhibited. He was born in Connecticut in 1740 to a broken family. He would rob nests, torture animals, and spread glass on the road to see children cut their feet, just for sport. He ran away from home at 16, and had a temper that would rage at the slightest provocation. He was insulted if not given the highest command, as noted at Ticonderoga. He was valuable in war, known as a wild man, and unwilling to surrender or yield to the enemy, inspiring novices to become warriors.

Benedict Arnold is known as the traitor of America’s cause. This notoriety stained every positive attribute and heroism he exhibited. He was born in Connecticut in 1740 to a broken family. He would rob nests, torture animals, and spread glass on the road to see children cut their feet, just for sport. He ran away from home at 16, and had a temper that would rage at the slightest provocation. He was insulted if not given the highest command, as noted at Ticonderoga. He was valuable in war, known as a wild man, and unwilling to surrender or yield to the enemy, inspiring novices to become warriors.

Yet, as J.T. Headley wrote, “Friends and foes speak of him alike with scorn… but there is another lesson beside the guilt of treason to be learned from his history – that it is no less dangerous than criminal, to let party spirit or personal friendship, promote the less deserving over their superiors in rank.” In other words, let us not forget the injustice done to these heroes by those who insulted them and helped, with their scorn and base spirit, to spark the darkest corners of their character. Providence exposes, not just the hubris of pride, but the baseness of envy.

![]() The providential legacy of Ticonderoga is that, despite the shortcomings and egos of Allen and Arnold, the Continental Army under Washington received 59 cannon and mortars from the fort after Henry Knox led a march through the snow to retrieve them miraculously by March of 1776. Washington was then able to drive the British out of Boston at Dorchester Heights after fortifying it in one night.

The providential legacy of Ticonderoga is that, despite the shortcomings and egos of Allen and Arnold, the Continental Army under Washington received 59 cannon and mortars from the fort after Henry Knox led a march through the snow to retrieve them miraculously by March of 1776. Washington was then able to drive the British out of Boston at Dorchester Heights after fortifying it in one night.

God chooses to use those whose lives are marked by vengeance, revenge, and a lust for titles and power. He lets their exploits speak for themselves, but if they do not submit to His Lordship in their hearts, repenting of their pride or envy, they will suffer tremendous dishonor in this life, and even worse loss in the one to come.

Today we face the same pressures as the heroes in our past. Let us embrace godly discernment, having compassion on those whose backgrounds may spurn them to a longing for acceptance. May we not think too highly of ourselves (Romans 12:3), recognizing that God uses people, including us, without endorsing every aspect of our character.