On December 2, 1823, the Monroe Doctrine was proclaimed by President Monroe. It was the culmination of key ideas drawn from the Bible and articulated in the Reformation. Three words came to define the foreign policy of America and the application of the Monroe Doctrine: independence (rejecting interdependence), neutrality (rejecting intermeddling), and interposition (rejecting interventionism.) America’s independence kept us from being drawn into unnecessary wars. Neutrality kept us from taking advantage of war to increase global power. Interposition restricted us to defensive wars and limited intervention to our hemisphere within certain clear parameters.

On December 2, 1823, the Monroe Doctrine was proclaimed by President Monroe. It was the culmination of key ideas drawn from the Bible and articulated in the Reformation. Three words came to define the foreign policy of America and the application of the Monroe Doctrine: independence (rejecting interdependence), neutrality (rejecting intermeddling), and interposition (rejecting interventionism.) America’s independence kept us from being drawn into unnecessary wars. Neutrality kept us from taking advantage of war to increase global power. Interposition restricted us to defensive wars and limited intervention to our hemisphere within certain clear parameters.

The roots of our original foreign policy rested on the law of nations (Art. I, Sec. 8, Cl. 10). The Law of Nations, from the writings of Hugo Grotius (1583-1645), was an application of the Biblical injunctions of “loving one’s neighbor as oneself” and “doing unto others what you would have them do unto you.” James Wilson, delegate from Pennsylvania to the Constitutional Convention of 1787 and second only to James Madison in influence, also became an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court. His writings on the law of nations were instrumental at our nation’s founding. In 1790 he wrote:

The roots of our original foreign policy rested on the law of nations (Art. I, Sec. 8, Cl. 10). The Law of Nations, from the writings of Hugo Grotius (1583-1645), was an application of the Biblical injunctions of “loving one’s neighbor as oneself” and “doing unto others what you would have them do unto you.” James Wilson, delegate from Pennsylvania to the Constitutional Convention of 1787 and second only to James Madison in influence, also became an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court. His writings on the law of nations were instrumental at our nation’s founding. In 1790 he wrote:

“The law of nations is the law of sovereigns. In free states, such as ours, the sovereign or supreme power resides in the people… therefore… the law of nations is the law of the people…. When I say… the law of nations is the law of the people: I mean not that it is a law made by the people, or by virtue of their delegated authority…. I mean that, as the law of nature, in other words, as the will of nature’s God, it is indispensably binding upon the people.”

Two ideas asserted here give us clarity about the roots of America’s original foreign policy. Wilson observes that God’s will (law of nature and nature’s God) is binding on the people. In other words, the degree to which a people have God ruling in their hearts will be proportionate to a nation’s conduct internationally. Second, by implication, when the heart of a people changes, their conduct, as well as that of their nation, will change. After all, Jesus said “the kingdom of God is within you” (Luke 17:21). God governs the nations through His Kingdom operating within His people. There is no biblical justification for a centralized government to rule the nations from above.

Since we no longer follow most of these ideas in our nation today, it is legitimate to ask what happened and when. I believe that the turning point away from the original ideas of the Monroe Doctrine as outlined above was the signing of the Treaty of Paris on December 10, 1898, ending the Spanish-American War. The causes and consequences of this war would alter the foreign policy of the U.S. The rising popularity of imperialism drew its lifeblood from the theory of Darwinian evolution that had been increasingly applied to social and international relations.

The truths of America’s original foreign policy, which reached its peak with the Monroe Doctrine, were well-known in 1898, but were in hot debate now that Darwinian evolutionary ideas were being applied internationally. The “survival of the fittest” meant stronger nations should police weaker ones for their own good, and this was now to be global. Also, “manifest destiny” had taken on an imperialistic justification. The final ratification of this treaty in the Senate was by one vote above the two-thirds required, and President McKinley signed it only after he changed his originally stated views.

Initially, the Monroe Doctrine stipulated that the U.S. would intervene in this hemisphere if a nation won its own independence decisively; and the new government was recognized. Furthermore, colonies of one empire could not become colonies of another by force or conquest. These applications were initially developed by John Quincy Adams as Secretary of State under Monroe. The causes of the Spanish-American War were suspect since the U.S. intervened before the steps above were followed in Cuba. Subsequently, the results of the treaty brought Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines under U.S. oversight as colonies with no promise of becoming States. This was the height of hypocrisy, since we fought England because she held us as a colony with no right of independence or self-government!

President McKinley, a professing Christian, wrestled with pressure from both businessmen as well as Christian leaders to change his foreign policy as he pondered signing the treaty. Businessmen wanted monopolistic profits, and Christian leaders thought that imperialism would benefit missionary activity. McKinley reported to a Methodist delegation that “in answer to his earnest prayers for guidance the revelation had one night come to him that ‘there was nothing left for us to do but to take them all, and to educate the Filipinos, and uplift and civilize and Christianize them, and by God’s grace do the very best we could by them as our fellow-men for whom Christ also died.’”

President McKinley, a professing Christian, wrestled with pressure from both businessmen as well as Christian leaders to change his foreign policy as he pondered signing the treaty. Businessmen wanted monopolistic profits, and Christian leaders thought that imperialism would benefit missionary activity. McKinley reported to a Methodist delegation that “in answer to his earnest prayers for guidance the revelation had one night come to him that ‘there was nothing left for us to do but to take them all, and to educate the Filipinos, and uplift and civilize and Christianize them, and by God’s grace do the very best we could by them as our fellow-men for whom Christ also died.’”

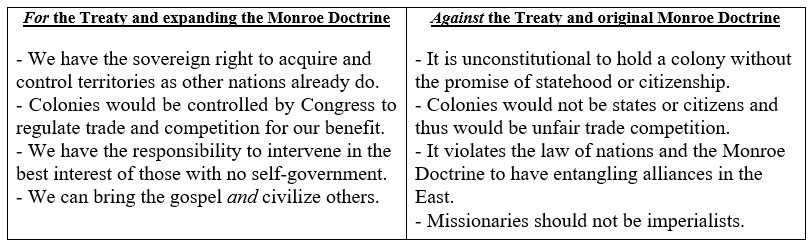

Though motivated by evangelism and sincere prayer, McKinley’s decision planted the seed that a love of money and souls were righteous reasons for imperialism. In essence, it was a return to the spirit of the “doctrine of discovery” rejected by the Pilgrims long ago, and which had set the precedent for a non-imperialistic policy among the nations. The Philippines, for example, as would be expected, revolted against American military rule as they had against Spanish rule. A summary of the debates in 1899 is as follows:

Though motivated by evangelism and sincere prayer, McKinley’s decision planted the seed that a love of money and souls were righteous reasons for imperialism. In essence, it was a return to the spirit of the “doctrine of discovery” rejected by the Pilgrims long ago, and which had set the precedent for a non-imperialistic policy among the nations. The Philippines, for example, as would be expected, revolted against American military rule as they had against Spanish rule. A summary of the debates in 1899 is as follows:

So, what can we learn? Though McKinley’s beliefs were sincere, he violated both the Constitution and the heart of the Monroe Doctrine. His decision changed history, planting the seeds of a movement toward imperialism in foreign policy that had already taken root domestically. We may decry the domestic “welfare state” where people become dependent on government. But we must also learn that a domestic welfare state becomes an international “warfare state” if left unchecked. Righteous motives must be accompanied by righteous methods.

So, what can we learn? Though McKinley’s beliefs were sincere, he violated both the Constitution and the heart of the Monroe Doctrine. His decision changed history, planting the seeds of a movement toward imperialism in foreign policy that had already taken root domestically. We may decry the domestic “welfare state” where people become dependent on government. But we must also learn that a domestic welfare state becomes an international “warfare state” if left unchecked. Righteous motives must be accompanied by righteous methods.

May we begin the process of restoration by repenting of our arrogance in fostering an entitlement society both here and abroad. Let us be a light to the nations by our example of serving others through private charity in the name of Christ and only for His glory.