About two weeks before March 23, 1775, when Patrick Henry would deliver his most famous speech, his wife Sarah had passed away after an awful mental illness where she had to be restrained from hurting herself. St. John’s Church in Henrico Parish was the only building large enough to hold the 2nd Virginia Convention on March 20. Henry was absent when he was elected as a delegate to the convention. His grief was so great that he confided with his physician that he was “a distraught old man.” A sorrowful and grieving Patrick Henry drew from the well of conviction for liberty with one of the most famous speeches of all time.

About two weeks before March 23, 1775, when Patrick Henry would deliver his most famous speech, his wife Sarah had passed away after an awful mental illness where she had to be restrained from hurting herself. St. John’s Church in Henrico Parish was the only building large enough to hold the 2nd Virginia Convention on March 20. Henry was absent when he was elected as a delegate to the convention. His grief was so great that he confided with his physician that he was “a distraught old man.” A sorrowful and grieving Patrick Henry drew from the well of conviction for liberty with one of the most famous speeches of all time.

But Patrick Henry didn’t just suddenly appear on the scene at the convention. His convictions for both religious and civil liberty ran deep from his experiences growing up, though his early life gave little indication of his intellectual or oratory skills. His father, John, was a county surveyor, the presiding magistrate of Hanover County, and colonel of Hanover’s state militia. His mother, Sarah, mastered the art of conversation, which she passed on to Patrick. Though books and Patrick were not fond of one another early in life, he was tutored by his uncle and mastered reading, writing, arithmetic, Greek, and Latin. George Morgan wrote, “He was a normal boy, who liked work as little as a colt likes the cart. Unaware of his own latent powers, he did as other boys in Hanover were doing – went barefoot in summer, fished, swam, sang, fought, did ‘chores’, and in fall and winter roamed forests with his flintlock.”

Though his father was a member of the Anglican (or “established”) church, his mother was a Presbyterian and took Patrick to hear Rev. Samuel Davies when he was 12. She would quiz him on the way home on Calvinist theology, but what impressed Patrick most of all was Davies’ oratory skills. He later commented that Davies was “the greatest orator” he had ever heard. Patrick Henry’s character traits of being inoffensive and conciliatory, and of having good manners, decorum, and good humor, allowed him to “transfuse into the breast of others the emotions… grand impressions in the defense of liberty.”

Patrick married Sarah Shelton in 1754, when he was 18. His initial years working his family farm and country store were disasters since he loved to talk more than make a profit. He turned his attention to law and, through the grit of self-effort, passed the bar in 1760. By 1763, his practice had doubled, and he was able to pay off his debts. His studies produced a conviction for natural law, the foundation for God-given rights, and a practice of the common law. Since the Anglican Church was supported through taxation, when the clergy sued the Vestrymen for reducing their salary, Patrick Henry defended a Thomas Johnson against the Rev. Maury. Since only a legislative assembly has the right to tax, he won the case of the “Parson’s Cause!” As David Vaughn wrote, “Thus, the celebrated case that led to Henry’s professional independence led also to America’s political independence.”

Patrick married Sarah Shelton in 1754, when he was 18. His initial years working his family farm and country store were disasters since he loved to talk more than make a profit. He turned his attention to law and, through the grit of self-effort, passed the bar in 1760. By 1763, his practice had doubled, and he was able to pay off his debts. His studies produced a conviction for natural law, the foundation for God-given rights, and a practice of the common law. Since the Anglican Church was supported through taxation, when the clergy sued the Vestrymen for reducing their salary, Patrick Henry defended a Thomas Johnson against the Rev. Maury. Since only a legislative assembly has the right to tax, he won the case of the “Parson’s Cause!” As David Vaughn wrote, “Thus, the celebrated case that led to Henry’s professional independence led also to America’s political independence.”

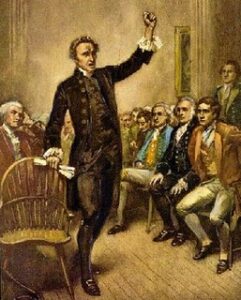

Chosen to fill a vacancy, he was a member of the House of Burgesses arguing against the Stamp Act in May of 1765. In defending the natural rights of Englishmen, he argued at the very root of the principle and his conclusion became memorable: “Caesar had his Brutus; Charles the First, his Cromwell; and George the Third (‘treason,’ shouted the speaker. ‘Treason, treason,’ rose from all sides of the room. The orator paused in stately defiance… without the least flinching from his own position,) – ‘may he profit by their example… and if this be treason, make the most of it.’”

Chosen to fill a vacancy, he was a member of the House of Burgesses arguing against the Stamp Act in May of 1765. In defending the natural rights of Englishmen, he argued at the very root of the principle and his conclusion became memorable: “Caesar had his Brutus; Charles the First, his Cromwell; and George the Third (‘treason,’ shouted the speaker. ‘Treason, treason,’ rose from all sides of the room. The orator paused in stately defiance… without the least flinching from his own position,) – ‘may he profit by their example… and if this be treason, make the most of it.’”

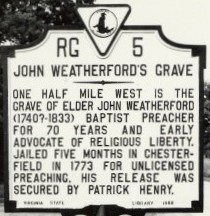

The most revealing of his convictions came in 1773 surrounding the case of Pastor John Weatherford, a Baptist, who as James Taylor wrote, “…became at once a zealous and successful herald of the cross… the rulers of the Episcopal Church were much vexed at the success… his ministry was attended by crowds and many were converted… it was his honor to suffer persecution for the sake of Christ.” Over 50 Baptist churches sprung up in a few months! Since he was preaching without a license, he was put in prison in May of 1773. After he had been in jail five months, Henry took his case at no charge and won it, but the jailer wouldn’t release him without his fines paid. In defiance of the injustice, Pastor Weatherford would not pay. Someone paid his fine and he was released! It was Patrick Henry.

The most revealing of his convictions came in 1773 surrounding the case of Pastor John Weatherford, a Baptist, who as James Taylor wrote, “…became at once a zealous and successful herald of the cross… the rulers of the Episcopal Church were much vexed at the success… his ministry was attended by crowds and many were converted… it was his honor to suffer persecution for the sake of Christ.” Over 50 Baptist churches sprung up in a few months! Since he was preaching without a license, he was put in prison in May of 1773. After he had been in jail five months, Henry took his case at no charge and won it, but the jailer wouldn’t release him without his fines paid. In defiance of the injustice, Pastor Weatherford would not pay. Someone paid his fine and he was released! It was Patrick Henry.

In 1774 the First Continental Congress took place in Philadelphia. Patrick Henry declared that, “All governments are dissolved… The distinctions between Virginians, Pennsylvanians, New Yorkers, and New Englanders are no more… I am not a Virginian, but an American.” David Vaughn noted: “That patriotic utterance was in truth a prophecy of the future United States of America.” His statement of unity in the cause of liberty inspired others to unite more intensely.

On March 23, 1775, at St. John’s Church, Patrick Henry rehearsed all these convictions and more in a speech that was later heralded as “perhaps the greatest political speech in American history.” After moving that “a well-regulated militia… is the natural strength and only security of a free government…,” which was seconded by Richard Henry Lee, some insisted that it went too far, and then Henry spoke:

On March 23, 1775, at St. John’s Church, Patrick Henry rehearsed all these convictions and more in a speech that was later heralded as “perhaps the greatest political speech in American history.” After moving that “a well-regulated militia… is the natural strength and only security of a free government…,” which was seconded by Richard Henry Lee, some insisted that it went too far, and then Henry spoke:

“…I should speak forth my sentiments freely, and without reserve. This is not time for ceremony. The question before the House is one of awful moment for this country…. Are we disposed to be of the number of those who, having eyes, see not, and having ears, hear not, the things which so nearly concern their temporal salvation? …I have but one lamp by which my feet are guided, and that is the lamp of experience. I know of no way of judging the future by the past…. Suffer not yourselves to be betrayed with a kiss….

If we wish to be free; if we mean to preserve inviolate those inestimable privileges for which we have been so long contending; if we mean not basely to abandon the noble struggle in which we have been so long engaged… we must fight! I repeat it, sir – we must fight! An appeal to arms, and to the God of Hosts, is all that is left us….

We shall not fight our battles alone. There is a just God who presides over the destinies of nations, and who will raise up friends to fight our battles for us. The battle, sir, is not to the strong alone; it is to the vigilant, the active, the brave…. Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take, but as for me, give me liberty, or give me death!”

Hearing Patrick Henry were George Mason, Thomas Jefferson, and George Washington, among others – and all were stirred and impacted. As historian David Vaughn wrote, “The convention sat in stunned silence, as if they had heard the voice of heaven, ‘for Henry had called them to the bar of judgment.’”