Thomas Weston financially backed the Pilgrims and their voyage to the shores of New England. He was attracted to the Pilgrims because they came as families under a church covenant. This, he believed, would prove to be the best atmosphere for an investment that was risky, especially since many plantations did not have an outcome that was prosperous. He may have been attracted to the Pilgrims’ character, but he certainly he did not embrace much of it himself.

Thomas Weston financially backed the Pilgrims and their voyage to the shores of New England. He was attracted to the Pilgrims because they came as families under a church covenant. This, he believed, would prove to be the best atmosphere for an investment that was risky, especially since many plantations did not have an outcome that was prosperous. He may have been attracted to the Pilgrims’ character, but he certainly he did not embrace much of it himself.

God seemed to provide contact with the Pilgrims when they needed it most. It became evident after he abruptly changed their contract, that he treated them “fitter for thieves & bondslaves than honest men.” As Arlene Spencer has noted, Weston “was a failing businessman who was terrible with money.” Thomas Weston had a habit of putting profit before his professed faith, recruiting others with similar character defects. As Bradford noted, God uses trials like these in their associations for His purposes: “That their children may see with what difficulties their fathers wrestled in going through these things in their first beginnings; and how God brought them along.”

After the Pilgrims were settled, Weston sent a ship in 1622 to establish a trading company separate from the Plimoth colony. The Pilgrims observed that the character of those that came could not sustain trade since their motive was only profit and they were willing to gain it by theft. Bradford wrote: “They had not been long from us, ere the Indians filled our ears with clamors against them, for stealing their corn, and other abuses conceived by them… we knew no means to redress those abuses, save reproof, and advising them to better walking, as occasion served.”

After the Pilgrims were settled, Weston sent a ship in 1622 to establish a trading company separate from the Plimoth colony. The Pilgrims observed that the character of those that came could not sustain trade since their motive was only profit and they were willing to gain it by theft. Bradford wrote: “They had not been long from us, ere the Indians filled our ears with clamors against them, for stealing their corn, and other abuses conceived by them… we knew no means to redress those abuses, save reproof, and advising them to better walking, as occasion served.”

Furthermore, the ships that did come from Weston had few supplies. After eating up much stores at Plimoth, they set up a settlement at a place the Natives called Wessaguset (later called Weymouth). Weston’s help proved “…a slender performance of his former late promise…. Remember what the Psalmist saith, Psalm cxviii.8, ‘It is better to trust in the Lord than to have confidence in man.’”

When Weston’s ship entered the harbor with these men, Bradford was deliberating with Massasoit about the mischievous conduct of Squanto. Bradford could hardly afford to lose his interpreter even though his conduct was deceptive. The interruption, however, probably saved Squanto’s life. But Squanto’s character was only a precursor to the disaster at Wessaguset by March of 1623. Bradford writes:

“It may be thought strange that these people should fall to those extremities in so short a time; being left completely provided when the ship left them, and had an ambition by that moiety of corn that was got by trade, besides much they got of the Indians where they lived, by one means and other. It must needs be their great disorder, for they spent excessively whilst they had or could get it…. By which their carriages (conduct) they became contemned and scorned by the Indians…”

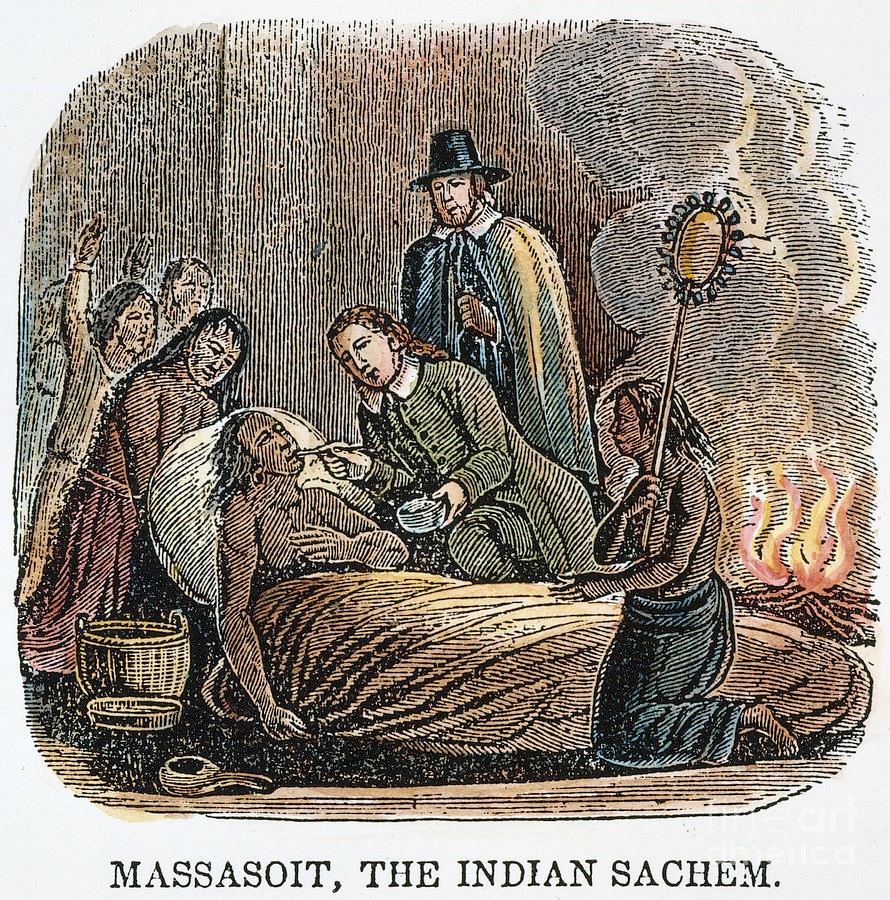

During this time, the Plimoth colony found out that Massasoit was ill. Edward Winslow and two companions, one of whom was Hobbomock as guide (Squanto had died), went to visit him. Some natives had told Massasoit that the English only were “friends” for what they could get, and would not visit in his sickness. After watching Winslow and others serve him as well as minister the herbs and cleansing to others, Winslow writes, “…upon his recovery, he brake forth into these speeches: Now I see the English are my friends and love me; and whilst I live, I will never forget this kindness they have showed me.”

During this time, the Plimoth colony found out that Massasoit was ill. Edward Winslow and two companions, one of whom was Hobbomock as guide (Squanto had died), went to visit him. Some natives had told Massasoit that the English only were “friends” for what they could get, and would not visit in his sickness. After watching Winslow and others serve him as well as minister the herbs and cleansing to others, Winslow writes, “…upon his recovery, he brake forth into these speeches: Now I see the English are my friends and love me; and whilst I live, I will never forget this kindness they have showed me.”

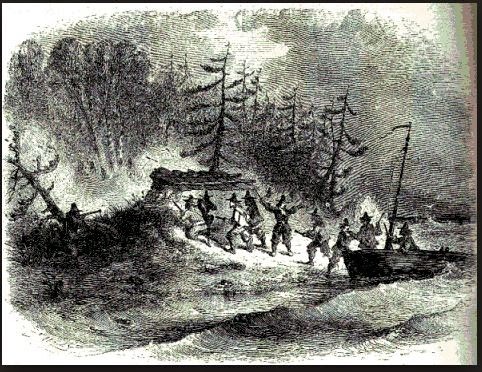

While Edward Winslow was with Massasoit, he told them of “the conspiracy of these Indians, how they were resolved to cut off Mr. Weston’s people for the continual injuries they did them, and would now take the opportunity of their weakness to do it, and for that end had conspired with other Indians their neighbors thereabout; and, thinking the people here would revenge their death, they therefore thought to do the like by them, and had solicited him to join with them.”

Massasoit even advised them “to prevent it, and that speedily, by taking some of the chief of them before it was too late.” Now they were in a predicament. Should they conduct a pre-emptive strike though no native had yet attacked them directly, especially being asked to do so by Massasoit? As they were taking this into “serious deliberation… in the meantime, came one of them from the Massachusetts with a small pack at his back.” This individual was Phileas Pratt, who had escaped and informed Plimoth of the truth of the dire situation and the imminent attack. Interestingly, Pratt wrote a Narrative, years later, as the sole survivor of Weston’s Colony that seemed to confirm what Massasoit had said.

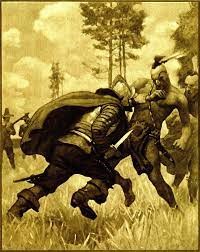

So, they “dispatched a boat away with Captain Standish and some men, who found them in a miserable condition, out of which he rescued them and helped them to some relief, cut off some few of the chief conspirators.”

So, they “dispatched a boat away with Captain Standish and some men, who found them in a miserable condition, out of which he rescued them and helped them to some relief, cut off some few of the chief conspirators.”

When Pastor Robinson heard of this raid and the shedding of blood, he wrote back and declared, “Concerning the killing of those poor Indians, of which we heard at first by report, and since by more relation. Oh, how happy a thing had it been, if you had converted some before you had killed any! Besides, where blood is once shed, it is seldom staunched of a long time after. You will say they deserved it. I grant it; but upon what provocations and invitements by those heathenish Christians? Besides, you being no magistrates over them were to consider not what they deserved but what you were by necessity constrained to inflict.”

Pastor Robinson was asking that they search their consciences as to whether they used too much force in contrast with sharing the gospel. Bradford concludes this drama by analyzing the need for true humility of character. He noted that Thomas Weston returned, in disguise, only to see his colony in ruin, writing:

“This was the end of these, that some time boasted of their strength (being all able, lusty men) and what they would do and bring to pass in comparison of the people here, who had many women and children and weak ones amongst them…. But a man’s way is not in his own power, God can make the weak to stand. Let him also that standeth take heed lest he fall (Romans 14:4; 1st Corinthians 10:12).”

Only humility of character, formed by the grace of God through the pressures of life, will stand the test of time. It was the Christian character of the key leaders of Plimoth that allowed them to survive in the midst of turmoil. This was difficult, since they received chastisement from their Pastor later but had to make a decision to defend themselves from a conspiracy at the urging of Massasoit. At times we all must make difficult decisions that may appear rash later on. Let’s remember that our profession of faith is best received when our character matches our profession. Oh, how we need to heed this lesson today!