On January 10, 1920, the League of Nations was founded by the Paris Peace Conference that ended the First World War. The initial covenant of the League was signed on June 28, 1919 as a part of the Treaty of Versailles. One of the chief architects of both the Treaty and the League, and the recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize for initiating the organization to prevent future wars, was President Woodrow Wilson. However, he would never see the U.S. join in his lifetime. Was this because, as it is written today, the U.S. was isolationist, or were there more important reasons?

On January 10, 1920, the League of Nations was founded by the Paris Peace Conference that ended the First World War. The initial covenant of the League was signed on June 28, 1919 as a part of the Treaty of Versailles. One of the chief architects of both the Treaty and the League, and the recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize for initiating the organization to prevent future wars, was President Woodrow Wilson. However, he would never see the U.S. join in his lifetime. Was this because, as it is written today, the U.S. was isolationist, or were there more important reasons?

President McKinley’s change in our original foreign policy had allowed us to accept colonies without the promise of statehood. This violated the original Law of Nations. Our departure from the Law of Nations continued with the way we acquired the six-mile strip to build the Panama Canal. The goal of building a canal was worthy, but the method used in getting Columbia to have her colony cooperate was wrong. The Monroe Doctrine required that Panama would have to win her independence and establish a stable government for a length of time before the U.S. could intervene militarily. Panama did revolt, but the speed at which President Teddy Roosevelt recognized Panama and blocked Columbia, as historian Julius Pratt observes, caused her to believe “she had suffered a grievous wrong at the hands of the United States.”

Sadly, interventionism for the good of the U.S. was becoming habitual. Though Teddy Roosevelt did some very good things, his Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine (to be a global, good nation punishing wicked ones for “chronic wrong-doing,” and “walking softly but carrying a big stick” for the purpose of preventing war) unfortunately made the U.S. the policeman of the world.

Sadly, interventionism for the good of the U.S. was becoming habitual. Though Teddy Roosevelt did some very good things, his Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine (to be a global, good nation punishing wicked ones for “chronic wrong-doing,” and “walking softly but carrying a big stick” for the purpose of preventing war) unfortunately made the U.S. the policeman of the world.

When World War I broke out in Europe in 1914, President Wilson pushed our foreign policy even further away from the Law of Nations. Intervention was justified to promote democracy. Wilson proclaimed neutrality on August 4, 1914 and won reelection on the slogan “he kept us out of war.” However, the definition of neutrality had been altered. Instead of withholding support from either side, U.S. businesses could sell to one side, and one side could borrow from our banks. Wilson’s speech of “Peace Without Victory” on January 22, 1917 was a new philosophy of collective security. After the sinking of three American merchant ships, though, the U.S. declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917.

On January 8, 1918, President Wilson addressed Congress with his “fourteen point” speech. Although emphasizing positive points of protecting “freedom of the seas and free trade and the concept of national self-determination,” he asserted that the method of protection would be to forcefully dismantle empires, create new states, and most importantly (as the WWI Museum states) form a “‘general association of nations’ that would offer ‘mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small nations alike.’” Once the war ended with an Armistice (11/11/1918), Wilson – without consulting the Senate as prescribed by the Constitution (Article II, Section 2, Cl 2) – took bold leadership to get the nations to adopt the Treaty of Versailles, with membership in the League of Nations as a requirement.

Defying all semblance of the Law of Nations, Germany was not even allowed to negotiate with the victors, and reparations of “war indemnities” laid the seeds of vengeance that would more easily sprout two decades later. There was no just resolution, and the Armistice – or ceasefire – symbolized a halting of hostilities, not an end to them.

Defying all semblance of the Law of Nations, Germany was not even allowed to negotiate with the victors, and reparations of “war indemnities” laid the seeds of vengeance that would more easily sprout two decades later. There was no just resolution, and the Armistice – or ceasefire – symbolized a halting of hostilities, not an end to them.

Wilson was a hero in the sight of the American people because he would end all wars. If the President was so popular, and the movement toward a new foreign policy so strong, why didn’t the Senate approve the League of Nations and ratify the Treaty of Versailles? In short, it was because the Senate was still elected by State Legislatures and most of its members, as a result, stood for principles of the Law of Nations and the Monroe Doctrine.

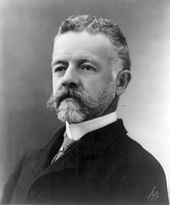

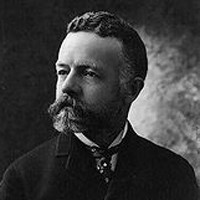

Senator Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts took the lead in opposing the ratification of the Treaty of Versailles and membership in the League of Nations. On February 28, 1919, he declared, “No question has ever confronted the United States Senate which equals in importance that which is involved in the League of Nations intended to secure the future peace of the world.” His first major point in opposition to the League’s constitution was that we would “abandon… the policy laid down by Washington in his Farewell Address and the Monroe Doctrine.” Washington advocated neutrality among the nations, and the Monroe Doctrine limited, under clear parameters, the only time the U.S. ought to interpose on behalf of nations in our hemisphere. Were we now to abandon these ideas?

Senator Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts took the lead in opposing the ratification of the Treaty of Versailles and membership in the League of Nations. On February 28, 1919, he declared, “No question has ever confronted the United States Senate which equals in importance that which is involved in the League of Nations intended to secure the future peace of the world.” His first major point in opposition to the League’s constitution was that we would “abandon… the policy laid down by Washington in his Farewell Address and the Monroe Doctrine.” Washington advocated neutrality among the nations, and the Monroe Doctrine limited, under clear parameters, the only time the U.S. ought to interpose on behalf of nations in our hemisphere. Were we now to abandon these ideas?

Lodge, objecting to the League, stated that nations would have to “guarantee the territorial integrity and the political independence of every member of the League.” He went on to say, “That means that we ultimately guarantee the independence and the boundaries, as now settled or as they may be settled by the treaty with Germany, of every nation on earth.” He stated that submitting to the League would mean that we would “give to other nations the power to say who shall come into the United States and become citizens of the Republic.” Lodge reiterated that collective security meant dissension would be increased since each nation only had one vote, yet were quite diverse. Furthermore, from tariffs, to taxes, to mandates, there appeared to be no way a nation could refuse or withdraw without abandoning it entirely.

Toward closing, Lodge made this declaration: “Unless some better constitution for a league than this one can be drawn, it seems to me… the world’s peace would be much better, much more surely promoted, by allowing the United States to go on under the Monroe Doctrine, responsible for the peace of this hempisphere, without any danger of collision with Europe….” In other words, following the Law of Nations and the Monroe Doctrine can resolve conflicts without centralized control over the nations.

Later in the year, Lodge spoke these words as an epitaph: “The United States is the world’s best hope, but if you fetter her in the interests and quarrels of other nations, if you tangle her in the intrigues of Europe, you will destroy her power for good, and endanger her very existence. Leave her to march freely through the centuries to come, as in the years that have gone. Strong, generous, and confident, she has nobly served mankind. Beware how you trifle with your marvelous inheritance; this great land of ordered liberty. For if we stumble and fall, freedom and civilization everywhere will go down in ruin.”

Later in the year, Lodge spoke these words as an epitaph: “The United States is the world’s best hope, but if you fetter her in the interests and quarrels of other nations, if you tangle her in the intrigues of Europe, you will destroy her power for good, and endanger her very existence. Leave her to march freely through the centuries to come, as in the years that have gone. Strong, generous, and confident, she has nobly served mankind. Beware how you trifle with your marvelous inheritance; this great land of ordered liberty. For if we stumble and fall, freedom and civilization everywhere will go down in ruin.”

Now, a hundred years later, we have indeed stumbled. But there is hope, since nations are ultimately extensions of individuals. If we begin treating each of our neighbors with respect and do all we can to effect change in the power of Christ’s love, the consequences will be national.