Following the creation of the U.S. Navy in October, the Continental Congress formed the Continental Marines on November 10, 1775:

Following the creation of the U.S. Navy in October, the Continental Congress formed the Continental Marines on November 10, 1775:

“That two battalions of Marines be raised consisting of one Colonel, two Lieutenant-Colonels, two Majors and other officers, as usual in other regiments; that they consist of an equal number of privates as with other battalions, that particular care be taken that no persons be appointed to offices, or enlisted into said battalions, but such as are good seamen, or so acquainted with maritime affairs as to be able to serve for and during the present war with Great Britain and the Colonies, unless they are dismissed by Congress.”

Initially, five companies of 300 Marines were raised by December. Originally intended to be drawn from the Continental Army for an amphibious invasion of Nova Scotia, they joined Commodore Esek Hopkins of the Continental Navy on its first squadron cruise.

Initially, five companies of 300 Marines were raised by December. Originally intended to be drawn from the Continental Army for an amphibious invasion of Nova Scotia, they joined Commodore Esek Hopkins of the Continental Navy on its first squadron cruise.

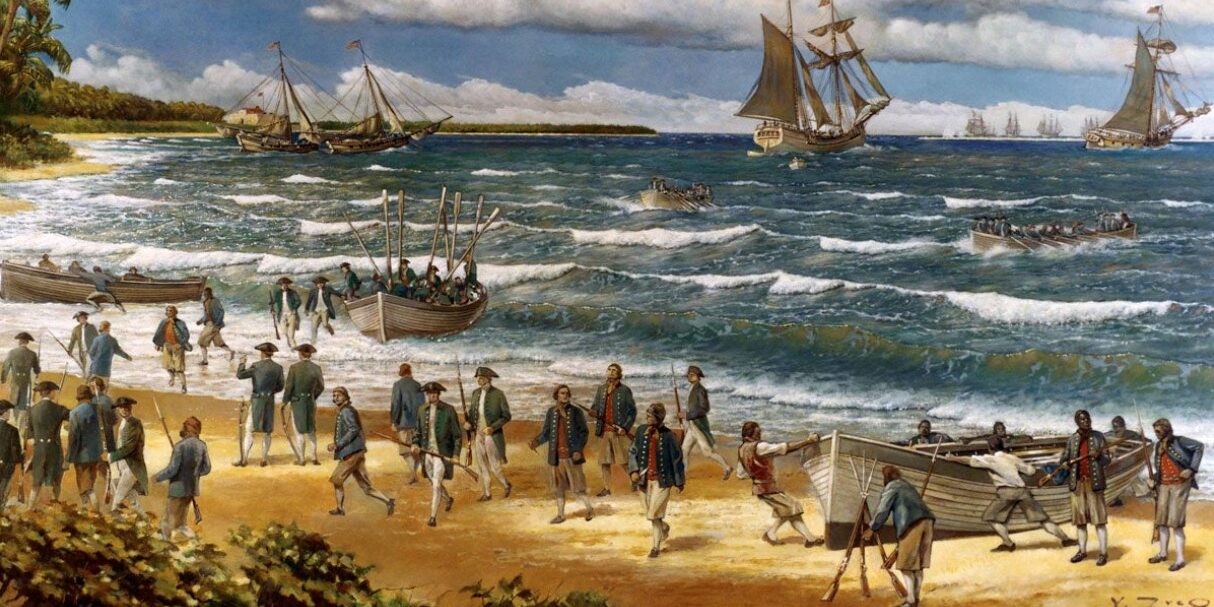

The Battle of Nassau in March of 1776 became the first amphibious invasion. The Marines captured two forts, the Government House, and a large store of supplies. However, what they did not get but needed most was gunpowder, a primary focus of this invasion.

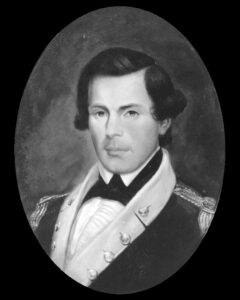

Though Commodore Hopkins was essentially the Commander in Chief of the Navy, he had in his squadron of eight ships Commodore Samuel Nichols, the first Commandant of the Marine Corps. Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1744, he lost both of his parents by the time he turned 7. He was taken in by his uncle, Attwood Shute, who was Mayor of Philadelphia.

Though Commodore Hopkins was essentially the Commander in Chief of the Navy, he had in his squadron of eight ships Commodore Samuel Nichols, the first Commandant of the Marine Corps. Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1744, he lost both of his parents by the time he turned 7. He was taken in by his uncle, Attwood Shute, who was Mayor of Philadelphia.

On November 28, 1775, the Continental Congress commissioned Nichols as “Captain of the Marines.” On this expedition in February of 1776, he assumed command of the Marine detachment on the ship Alfred. He successfully landed his 234 Marines and was part of the first successful landing without a fight, but the show of force helped turn the tide of public opinion toward the hope of victory.

Nichols was promoted to major by the Continental Congress in June of 1776 and was sent by Commodore Hopkins to Philadelphia, where he reported to the Marine Committee. His first assignment was to recruit and “to discipline four companies of Marines and prepare them for service as Marine guards for the frigates on the stocks.” Having completed this task, he requested arms and equipment for them to carry on their duties.

Nichols was promoted to major by the Continental Congress in June of 1776 and was sent by Commodore Hopkins to Philadelphia, where he reported to the Marine Committee. His first assignment was to recruit and “to discipline four companies of Marines and prepare them for service as Marine guards for the frigates on the stocks.” Having completed this task, he requested arms and equipment for them to carry on their duties.

The Marines eventually served flying the Don’t Tread on Me flag created by Christopher Gadsen, a delegate from South Carolina. He gave it to Commodore Hopkins to fly on the Alfred, but it was then utilized by the Marines. The coiled rattlesnake represented the unity of the Colonies in their defense against tyranny. In December of 1776, Major Nichols wrote to Congress that he was ordered to march three companies to be directly under the Commander in Chief, General Washington. This would have put the Marines under the command of the Army.

More importantly, it would establish the fact that though the Marines had trained for sea battles and landing expeditions, they would now need to train for land campaigns. William Fahey writes in his book review of Bohm’s work, Washington’s Marines: The Origin of the Corps and the American Revolution 1775-1777, that the nation “wanted men of honor and excellence; it wanted a military force that was flexible, poised for action, and determined.” General Washington’s need for specialized fighters became the origin of what we now know of as our present Marine Corps and its motto “Semper Fidelis” (always faithful).

More importantly, it would establish the fact that though the Marines had trained for sea battles and landing expeditions, they would now need to train for land campaigns. William Fahey writes in his book review of Bohm’s work, Washington’s Marines: The Origin of the Corps and the American Revolution 1775-1777, that the nation “wanted men of honor and excellence; it wanted a military force that was flexible, poised for action, and determined.” General Washington’s need for specialized fighters became the origin of what we now know of as our present Marine Corps and its motto “Semper Fidelis” (always faithful).

The early years of the Marine Corps serving General Washington at a critical time with the crossing of the Delaware and the successful battles of Trenton and Princeton during his “ten crucial days” (December 25, 1776 to January 3, 1777) are often neglected, being overshadowed by the Army’s role. Fahey writes, “For Bohm… these years are a tale of Marines at their best – serving ‘a critical role in the American Revolution. Rushing to the aid of George Washington and the Continental Army in their most desperate hour, their actions helped turn the tide of the war .… In doing so, they established a legacy that generations of Marines strive to emulate to defend their great nation.’”

At a time when the Continental Navy was slowly building its frigates, and the Continental Army was facing daily dwindling numbers with only a dim hope of new recruits, the Continental Marines protected Philadelphia, brought new morale to the Army, and with perseverance and determination to do whatever was necessary, filled the gap, “stood in the breach” and in the words of Bohm, was “flexible, elite, innovative, and bold.”

At a time when the Continental Navy was slowly building its frigates, and the Continental Army was facing daily dwindling numbers with only a dim hope of new recruits, the Continental Marines protected Philadelphia, brought new morale to the Army, and with perseverance and determination to do whatever was necessary, filled the gap, “stood in the breach” and in the words of Bohm, was “flexible, elite, innovative, and bold.”

Nichol’s Marines were assigned to cross the Delaware south of Trenton as Washington did on the northern side, but had to turn back due to ice. Undeterred by this discouragement, they arrived in time to participate at the Battle of Princeton. Following this victory, they continued with infantry and artillery roles, and after the British evacuated Philadelphia in 1778, their recruitments resumed. During the War for Independence, there were 131 Colonial Marine officers and about 2,000 enlisted Marines. Their uniforms, not officially established until September 5, 1776, distinguished them from the blue coats of the Army and Navy. The Marines were officially disbanded in 1785, but re-established in 1798.

The Marine’s Hymn, official hymn of the Marine Corps, authorized in 1929, has as part of its lyrics “first to fight for right and freedom, and to keep our honor clean.” The prophet Ezekiel articulated the heart of God in this regard of being first to fill the gap: “The people of the land have used oppressions, committed robbery, and mistreated the poor and needy; and they wrongfully oppress the stranger. So, I sought for a man among them who would make a wall and stand in the gap before Me on behalf of the land, that I should not destroy it; but I found none” (Ezekiel 22:29-30).

Standing in the gap is necessary and demands what the Marine Corps has always exhibited throughout its history – Semper Fidelis – always faithful! Jesus said, “He who is faithful in what is least is faithful also in much” (Luke 16:10). Lessons of faithfulness in our families, places of employment, and our neighborhoods are required these days. Faithfulness demands flexibility, determination, and boldness!